Think of a few top CEOs or entrepreneurs.

What path did they take to achieve their fame?

To what do they credit their success?

Outside of the generic, “hard work, self-belief, and never give up,” what did they do?

Did they develop habits?

Seek out business coaches?

Join a paid Facebook group?

Dedicate time to studying their industry?

Can you recall any top CEO or entrepreneur crediting their success to paying thousands of dollars to attend all-day meetings?

Consider the question for a moment.

Does Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, or Susan Wojcicki attribute their success to a group of like-minded hustlers? A group they paid thousands of dollars to join? A group that was run by a self-labeled business coach? Can you recall them saying, “If I didn’t pay that business expert $50,000 to join all-day meetings, I’d be nowhere today”?

I’ll tell you the answer.

No.

You might argue that some CEOs work with Tony Robbins. And you’re right. But those CEOs made it to the top of the heap without Tony’s expensive advice. To those CEOs, Tony is a status hire, a bragging right. Some successful people have a unique way of surrounding themselves with “experts.” One portion hire experts to make day-to-day tasks easier, like a chef. Whereas the others seem to combine peacocking with a quick fix for some existential crisis, like hiring a Shaman. Tony is expensive and hiring him signals status. “Tony Robbins is my life coach” rolls off the tongue nicely. Granted, Tony is arguably one of the best motivators in the world. And he resonates with a crowd who yearn to achieve. Yet when you study a successful company’s history, or a successful person’s rise, that success didn’t begin with Tony’s ideas. That success didn’t begin with a success coach. And that success certainly didn’t begin with a paid meeting called a mastermind.

Today, many people sell various success methods. The offerings range from meditation secrets to persuasion tactics that promise to “30x your business!” And masterminds are popular products offered by countless “business gurus,” “income experts,” “growth architects,” and “high-ticket closers.” They are sometimes called an “Inner Circle,” “Platinum Executive Club,” “War Room,” “High-Ticket Closers Circle,” and other clichéd names. No matter the name, they all operate on the basic mastermind concept.

What is a mastermind?

A mastermind’s core premise: an intimate meeting of like-minded professionals who share ideas to benefit your business and career. Some are free to join. But most of you must pay to join. They start at $5,000 and soar to and even over $100,000. Most meet once or up to four times a year. Now with most masterminds, but not all, that fee entitles a member to the total meetings sold. As in, if you joined a mastermind offering four meetings, you don’t need to attend each meeting in a given year. That’s part of the reason why most meetings will have some new faces and some old faces. While the mastermind’s sales page may claim to “close the doors,” that phrase has been bastardized into a call to action. Most gurus will keep the doors open; only a rare few actually do limit members.

All masterminds promise “new” secrets, high-level connections, and ways to explode your business. Paid masterminds offer a well-intended opportunity to grow your business. But in reality, you pay money to attend an all-day meeting and posture inside a social theater.

The mastermind idea originated with Napoleon Hill.1 In his book, Think and Grow Rich, Hill claimed that men like Andrew Carnegie met other industry titans in intimate settings to share ideas. Hill claimed that the ideas they discussed would then seed into the universe (as in, manifest your destiny). When ready, the ideas would impregnate the unconscious mind. After some gestation, they would birth miraculous business growth.

Hill isn’t wrong that Andrew Carnegie met with other wealthy men of his time. I’m sure Carnegie and his fellow Robber Barons discussed business. It’s probably no different than if you chat shop with someone working at a different company, or if Tim Cook asks Jeff Bezos for a new microchip supplier.

Yet mounting evidence shows that Hill never even met the titans, let alone joined their “secret business meetings.” My guess is that Hill added a sexy label to the obvious idea that Carnegie met others and talked business. He created a romantic, near conspiracy-sounding name—mastermind. It sounds almost like a syndicate (which is interesting, since most direct marketers call their insider groups that discuss how they will launch and sell products, syndicates).

Mastermind. It’s a romantic notion, isn’t it? A group of powerful and wealthy business owners meet to flesh out big ideas and complex plans. Their decisions affect the future. While we, the success-driven professionals, wish to taste those secrets. If you haven’t yet achieved the level of success you want in life, you can imagine sitting in a room with mentors who reveal untold secrets to success. Secrets you can ride to the loftiest heights.

Next, consider the alluring conspiracy essence: a group of powerful people meet in private like some entrepreneur Illuminati. They discuss secrets only known to them. Then those like-minded hustlers apply the secrets to control their destinies, all while getting stinking rich in the process.

Hill birthed the mastermind concept, but his followers monetized it. Hill himself never monetized masterminds. In fact, Hill never monetized much of anything. After Think and Grow Rich’s initial success, Hill finished his days destitute. Masterminds never quite hit their money-making stride until Gary Halbert came along in the 1980s.

Famous copywriter Gary Halbert added structure to Hill’s mastermind concept. Halbert developed the idea of a one-hour hot seat (footnote Gary Halbert Letters, and Dan Kennedy Seminars, and various stories I’ve heard at masterminds). A hot seat? An attendee gets one hour focused on them. The core idea: the expert and attendees will grill you about your business for one hour. That grilling supposedly cranks your business to new levels.

Halbert’s model and wild popularity influenced the mastermind we know today. People like Dan Kennedy, Joe Polish, Ryan Deiss, John Carlton, Frank Kern, Guthy-Renker (the company who created Tony Robbins), Yanik Silver, Jeff Walker, and Eben Pagan (David DeAngelo) were all influenced by Halbert’s model. And I’d argue that same group taught Russell Brunson. Every one of them recycled Gary’s basic mastermind structure, and some added in their own ingredients. A few created an event style mastermind, where the “expert” mainly “teaches.” Others created courses and masterminds selling “how to create and sell a mastermind.”

Here’s what’s shocking: despite people paying thousands upon thousands of shekels to learn how to create a mastermind, the concept is brain-dead simple. Gary Halbert supposedly came up with the idea while salting himself in a Florida Keys bar. He thought it’d be an easy way to make a lot of money without doing much work. And he was right.

Most masterminds or “Inner Circles” basically run Gary’s plan:

- Get between ten to twenty-five attendees—if you’re doing hot seats, best to keep it under twelve people.

- Offer a one-hour hot seat.

- Bring in a guest expert or two to present or attend.

- Host the event for two or three days.

- Sell “insider relationships,” “accountability,” and “how it will grow your business.”

- Charge money for it.

Let’s create a mastermind.

We return to Bill.

Bill is The Good Word’s fictional guru. Here’s a quick recap on Bill’s journey, which resembles most “online experts.”

- Bill originated as a personal trainer.

- He started an online side business selling fitness and weight loss info products.

- After nearly a decade, he wrote a sales letter that was seen as a hit inside ClickBank.

- The hit profited close to one million dollars in sales, and Bill netted a six-figure income.

- After a year, his “hit” offer foundered.

- Needed income to match his new money lifestyle, Bill slithered into selling “how to be successful,” also known as selling success.

Bill niche-hopped into selling success, a common step that many gurus take. Most gurus weren’t big giants in their fields or niches. At best, most were average and tasted some success, but then the bottom fell out. Yet they yearn to be seen as a big player. Like most gurus, Bill experienced mild success (a sales offer grossing close to or more than seven figures), but then he couldn’t recapture the magic.

We meet Bill reinventing.

Bill’s journey to becoming a business expert, like all success gurus, begins with reinvention. He is searching for a new image to show to the world. Bill wants to teach success, and he’s looking at how to position himself. He’s not pioneering new business advice. He’s not scrapping away as a consultant. He isn’t getting hired by Venture Capital firms to pitch huge deals. He isn’t getting called to draw companies out of bankruptcy. In other words, he isn’t hired to get results.

At the end of the day, Bill lacks skin in the game. As we know, Bill ran an information product launch business model tied to affiliate marketing. He did everything via a paint-by-numbers formula. Granted, he made money doing it, but Bill only knows that business model. He isn’t much of a copywriter. He isn’t much of a salesperson. He isn’t much of a leader.

When Bill can finally hire someone, people hate working for him. Why? He changes his management style and “employee culture” method each time he reads a new business book. In short, Bill is a socially awkward person who made some money selling info products on the internet. Like most success gurus, Bill has limited business know-how. He barely even knows his own business model. Bill learned the rest from the pseudo-business books you find in airport bookstores and on shows like Shark Tank. Still, Bill, like most gurus, sees himself as a business visionary.

When Bill moves from selling weight loss info products to selling business advice, he first creates some info products that sell success. He buys a done-for-you template that shows him how to create the offer, tells him which sales funnel to use, and even features the content that he will teach. The template also offers generic marketing tips like “find a hungry marketplace,” “join ClickBank and find affiliates,” or “try your hand at Facebook ads.”

A note on content: most standard guru make-money-online products include copywriting, mindset, goals, consulting, high-ticket sales closing, making money on social media, getting new leads, and public speaking. But the products are offer forward. Meaning, you write the sales message first. Then you look at the promises you made in the sales letter. Last, you try to create a product to solve the promises. It’s often taught that you should take no longer than two weeks to create the product. The key focus is the sales message. Many gurus have turned this formula into a paint-by-numbers plan that they sell.

Bill follows the paint-by-numbers marketing steps. As in, he creates the offer first. Once he has the offer, he looks at his promises. From that, he tries to create a product. The promise, again, doesn’t come from experience. Bill’s promise stems from his market research. And his research adheres to the standard digital marketing, direct marketing advice.

Bill, like most gurus and countless other digital marketing businesses, seeks out customer “pain points.” He creates a survey asking potential customers for their biggest problems. For instance, in weight loss, a problem might be, “I hate the rebound weight gain.” He also asks questions like, “What would it be like if this problem could be fixed?” and “What would be the best-case scenario answer to those problems?” As in, he asks questions to determine what his solution should look like.

Next, Bill may look at best-selling books on Amazon related to his niche. He’ll look at the language in the five-star reviews and the one-star reviews. He’s looking for what people loved about the results and where some people struggled. Last, Bill will study other competitor’s promises, or Unique Selling Propositions, in his potential marketplace. He will look for commonly made promises as well as other fad generalities he can use like, “With so many fake gurus out there telling you how to make money…” From here, he creates his promise, his hook, and his sales letter.

And as for the product?

Well, when a guru, like Bill, tries to create a product that pays off the promise, things get a little murky.

In his paint-by-numbers course, Bill learned three principles for creating his product:

-

You only need to be one step ahead of your market. This concept goes back to Gary Halbert seminars and likely back to Joe Karbo, who Halbert deeply admired. Robert Ringer also taught the idea. According to their teachings, you just need to know a bit more than who you’re selling to. That “bit more” doesn’t mean experience. Here’s how it plays out. The guru teaching Bill will state the standard lesson, “People love paying for information. And too many people waste time worrying about not being an expert. If you’ve never closed sales in person and you’re trying to sell a “high-ticket closers” product, just look up ‘how to close’ in a popular sales book. You’ll get enough information to lead the mastermind, and no one will know the difference. Most people don’t read or research things. Even if they read, most read poorly, and the info will seem new to them.” (FOOTNOTE countless masterminds, events, and courses.)

-

Sell them what they want. Give them what they need. As you can see, this is a meaningless statement, but it comes in various forms. You might hear, “They will forget the crazy promises, just give them whatever you know!” or “If you’re worried, something like only 3% actually ever go through the course. Most just buy it; 15% do like a module or two, and the rest do nothing with it.” In other words, don’t spend time worrying about a great product. They tell you that you need to get started because “action alleviates anxiety.” In other words, they dogmatically teach you to not worry about the product; just create the offer.

-

Create content that sells. Currently, this seems to the most popular method. Basically, gurus create content that works as a sales pitch to sell more products. Some gurus salt open-loops into a product. As in, a “better and faster way” is mentioned in the original product. But, to get that “better and faster way,” you must buy a more expensive product. How can you spot it? Listen to the guru talk about coaching. If he says something like, “The best investment is yourself,” he’s using his content to sell his products. Some gurus even learn to create courses or offer a “free” book that works as a sales page to sell more products. Really sharp gurus, like Ryan Deiss, can host an event like Traffic and Conversion, and the entire event sells products. The lessons tend to say little other than things anyone can say, like, “The best demand is when you’re in demand.” This “create content that sells” method links back to motivational speaking events, where the speaker’s talk is a guise that sells their product. And it links back to magalogs. Magalogs were a direct marketing method made popular by Rodale and Boardroom Publishing (now Bottom Line). A magalog is a sales pitch to some product or a few products. The articles never convey conclusive information. They just offer you a way to get the “miracle.” Just like the magalog, a guru’s course has one purpose: to get you to buy more products.

Bill focuses on the murky third method when creating his products.

Why?

If you read the first Bill post, you know that Bill depends heavily on Russell Brunson’s Clickfunnels product. Russell also sells various Expert Funnels.

Bill buys each one.

Inside the Clickfunnels software, you can buy product upgrades like Funnel University. In this upgrade, Russell or a Clickfunnels employee break down a certain sales funnel, such as Frank Kern’s or a retail store’s. Russell describes the funnel, how it works, and why he likes it. Then, if you’re a Funnel University subscriber, Clickfunnels gives you an option to use that funnel. You simply click a link, and—voila!—you have the entire funnel at your fingertips. Everything is paint-by-numbers, from the copy to the layout to the videos.

Bill buys those prepackaged funnels. Still, he needs to sell something. As we know, Bill lacks real-world experience—a fact he wildly misses.

So what does Bill do?

We know Bill is creating an offer-forward product. Now, it’s time for the key part of his offer: positioning. Bill needs to label his products and tie the name to a theme.

Why?

Again, positioning.

The theme helps position the products. As the theory goes, a theme like “Warrior Closing” aims at creating a position. Instead of just naming the product “Closing Sales,” you tie it to the guru’s shtick. You might know this as “branding.”

But in this world, branding isn’t the primary goal. In fact, to some, branding is seen as a waste of time. Why? Many direct marketing gurus view branding as a nine-to-five corporate thing. It makes little sense to me. Yet the theme, in the digital marketing world, and exponentially more in the guru world, is seen as positioning that boosts conversions.

That theme-based positioning is also tied to a copywriting tactic called mechanism. Here’s the short definition of mechanism: it’s the tangible part of the product that generates a repeatable result, like the aspirin in Excedrin that reduces pain. But in copywriting, the mechanism can twist the tangible—or the supposed tangible—into a tantalizing shortcut. “Weird trick to earn six figures in passive income working only one Sunday a month.” Here, in this shopworn phrase, the mechanism is something akin to a killer sales offer, Direct Messages on social media, or an investment scheme working so smoothly, you need to check on it once a month. Yes, it’s that vague and wildly unrealistic. The tantalizing shortcut? Copywriting skills, or some script to use on social media, or god-knows-what for an investment strategy. In short, the main goal is to elicit in their prospect’s mind that they offer a mechanism, a shortcut, a secret map, to the desired result. And the guru tries to create an ideology, or personal image, of how the prospect may get results. As in, they don’t just earn six figures. They earn it like a Warrior. So, all of the guru’s products must tie to the guru’s chosen shtick.

Bill works on creating the offer, and he tests various labels until he finds one that boosts conversions. He tailors his offer to the funnel Russell Brunson provides inside his Clickfunnels software. Once Bill has his label and his “how to make money online” course ready, he begins selling it. But, all that offer creation is aimed at one thing: live events.

The cornerstone step for gurus: hosting live events.

Bill knows he must host a live event. The mastermind product for someone like Bill is critical.

Distinctly critical.

A guru’s livelihood largely depends on live events. Their shtick—their claims on how they have coached entrepreneurs who command hundreds of millions of dollars—hinges on the people who pay to sit in a room and listen to them.

Bill starts with this formula: create a generic make-money course that sells the mastermind. This means that a course like “How To Start A Million Dollar Empire” aims at pushing his live events. Note, those courses sell other courses, yet they will all either hint at or directly sell a live event like a mastermind.

Why sell the course first and not the mastermind? Bill sells both. But he lacks the marketing chops to focus on directly selling the mastermind with a sales page. So, at this stage in his journey, selling the courses is an easier way to feed people to the live event. At some point, if Bill attracts a larger following and can hire better copywriters to write the sales pages, he will use various platforms to directly sell his mastermind. By using boilerplate templates, Bill funnels people into his live event. This is a tried and proven method that works for most “hot new gurus” on the scene.

The core aim is still to sell live events. The money resides in live events.

Live events generate profits in three different ways:

- Sell more products at the event that help sell other live events.

- Sell more exclusive live events.

- Feature guest experts who pay to speak. Or, the guru may pay them but gets a cut of their product sales. Gurus structure various deals here.

The mastermind is the easiest live event to start. Bill, and other gurus, call the mastermind “high ticket.” This means they can kill two birds with one stone. First, they sell the mastermind. In the direct marketing world, most products costing over five-hundred bucks are considered “high ticket.” A mastermind costs well over $5,000, so the guru uses the sales price from the mastermind to claim that he has closed high-ticket sales. Second, he turns this claim into a product by making it sound like the guru will teach guarded secrets of closing high-ticket sales. In sum, those “high-ticket closing” style products, yep, are tied back to the guru’s ability to sell a paid meeting. To the general public, we might call a high-ticket sale something like selling a Boeing airplane. But to gurus, high-ticket sales means selling their events.

A little sidetrack. Sales trainers or gurus who use a high-ticket closer theme almost always use a mastermind or coaching session to lay claim to that label. Most true “high-ticket closers” never call themselves that. Why? A person who deals in high stakes needs to be a professional. They must be seen on the same level as the person who structures the pending deal. This usually means rich companies and wealthy people. So, if a person has a “shtick” like “high-ticket closing master,” they’re seen either as a poser or a clown. Someone with a shtick has never done venture capital deals. Nor have they ever closed something like a commercial real estate deal in the mega millions. If you see the high-ticket closing label, it generally links back to a mastermind or the guru selling coaching.

How do you develop a mastermind?

To really make money, Bill knows he needs to create a mastermind. And, all of the new “products” he’s going to sell through his various expert funnels will push the mastermind.

Even though Bill belongs to a few masterminds, he’s nervous about starting one. Bill, like most gurus, loves optimization. He worships success secrets, success hacks, and success methods. He believes those things equate success. And Bill thinks “action alleviates anxiety” and believes the best investment is himself. Despite knowing and attending masterminds, Bill has no idea how to start one.

Bill decides he must invest in his success, so he joins another Russell Brunson Mastermind. This new mastermind is called How to Start a Mastermind. (Yes. Masterminds on how to start a mastermind exist.)

Bill eagerly listens to Russell. For the umpteenth time, Russell or someone gets on stage and shows the numbers that a mastermind can produce.

Here’s a basic overview.

- Label yourself an expert.

- Create a sales page selling a mastermind.

- Charge $20,000 to join.

- Get at least twenty people to join.

- 20 x $20,000 = $400,000

Bill sees this as alchemy. He thinks Russell is showing him a legal way to print money. He misses the fact that anyone can put up these numbers about anything. Instead, Bill sees these numbers as a viable business model.

Then Russell, being the showman he is, pours on the heat. He explains how easy it is to run a few of these events. Russell’s right. Russell then walks the numbers up to over $1,000,000. And Russell or a “guest expert” teaches Bill and the audience how, for just twenty hours of work, they can make $10,000,000.

The entrepreneurs furiously take notes. Russell even invites teenager and self-proclaimed eight-figure-earning financial wizard Caleb Maddix on stage.

Bill feels guilty.

Why hasn’t he made as much as Caleb? Bill—like most gurus and most people posting “100” on a guru’s Instagram page—believes Caleb’s claims. But then Bill realizes that feeling guilty is toxic thinking. If Caleb can make eight figures, then so can Bill. This, by the way, is why Russell pulls Caleb on stage. To get the reaction we just saw with Bill. It’s a powerful sales method.

Russell uses a prop like Caleb in two ways.

First, Russell is slyly selling his own credibility. Why? Russell is whale hunting. Whale hunting is a common tool that many sales people, from gurus to high-end consultants, use. It’s nothing nefarious. It’s when someone like Russell looks for one or two people in a room who can make him a lot of money. A consultant may host an event and look for the one or two people who will hire them for a huge fee, but Russell runs bloodthirsty partner schemes. He looks for potential businesses that he can partner with and take into the stratosphere. Russell’s a fox; one must pay Russell a lot to get this partnership. And as a cherry on top, Russell takes an enormous cut.

The second way Russell uses Caleb is for straight selling. He will use things like a speaker or a “lesson” to upsell either other events or more products. Someone like Caleb presses hard on the “invest in yourself” theory the people in this world fetishize. People feel guilty for not having been like Caleb when they were younger. They feel scared Caleb greatly outperforms them. They feel their only choice to better their situation is to invest in themselves by buying something that promises them faster ways to growth.

Bill’s hand cramps as he writes notes.

He’s practically drooling.

He can’t believe he found this alchemy.

He’s found a way to fame, prestige, and riches.

Then, Russell brings up another guest. This time, it’s someone with ties to Grant Cardone. And this mystery guy behind Grant Cardone shows Bill more alchemy. He says that if you run a few events with X many attendees, you can make up to $100,000,000.

Bill nearly falls out of his seat.

His hand cramps even more.

He pounds his Organifi Greens Drink to calm the cramps.

Bill looks around the room. He views himself as superior. He knows his routine is better. These people in the room probably hit the snooze button. Bill goes to bed at 7:00 p.m. and wakes up at 3:00 a.m. Bill has optimized his morning routine. Bill reads Og Mandino. Bill attends Tony Robbins events. Bill writes in a gratitude journal every night. He looks at the inferior snooze-button-hitting losers and sees himself as better. Bill envisions himself going above and beyond. He fancies that he can become a billionaire.

The mastermind product will probably be Bill’s biggest income generator. Bill will likely never become a billionaire. Yet masterminds do offer Bill the fastest way to make six figures or more. And they bring Bill closer to other critical guru-profit generators: events, consulting, stage-selling, co-hosted masterminds, and co-hosted events. These events combined will earn Bill a comfortable high-six-figure income. He’ll claim he’s a millionaire based on the profits. But Bill, like most gurus, ignores overhead costs and debts. Though, we can’t deny that Bill may possibly strike luck and make over one million dollars a year. He may even strike incredibly rare luck and get into the ranks of Grant Cardone, Tony Robbins, and Gary Vaynerchuck. But this is highly unlikely. Bill lacks the social swagger those giants innately pack. He also lacks a killer instinct.

Bill’s key to riches: success labels.

As Bill starts selling business advice, he learns that he needs to raise credibility. But credibility in the guru business looks different than common credibility. When we think of credibility, we think:

- Experience

- Industry leader

- Business model pioneer

- Track record of results

- Known for developing or improving a philosophy in their field

Generally, a track record comes with time. Certainly some people “get it” right away (like Jeff Bezos). Regardless, credibility is usually linked to an intelligent person with street-level know-how. We respect the person’s opinion, insight, and advice. We also respect that the person has skin in the game.

In the digital marketing guru and success world, credibility takes on an entirely different meaning.

Bill learns that he needs credibility for three reasons. The first, and most important, reason is that credibility labels help raise sales page and event conversions.

The next reason is that gurus use credibility labels for positioning. Bill learns from experts like Dan Kennedy or Frank Kern that he needs to position himself correctly. He must position himself as the expert. Trademarking this position, like labeling yourself “The Master Closer” or “The Billionaire Maker,” is hip right now.

Last, the credibility labels offer “proof.” Not proof of experience, but cosmetic proof that helps bolster a sales promise, boost conversions and center a Unique Selling Proposition (the benefit for choosing a product or guru compared to the competitors). It’s pseudo-proof. But to a guru, it’s real.

Why this “proof”? Because it makes it easier for the customer to fork over $20,000.

Now, experts like Dan Kennedy, Frank Kern, Ryan Deiss, or even Tony Robbins, peddle this “credibility” or “expertise” idea by saying that you can call yourself an expert and make money.

Why?

Gurus like Bill are gullible to the credibility pitch. Bill’s ego loves the idea of being seen as an expert. The labels give him something to get that validation. To the people selling those labels, Bill is a laydown customer. They tell him how the labels will boost his conversions. Then, they remind him that “the graveyard is full of credible experts too scared to sell themselves, experts scared to make money because of their poor mindset.” Then they hook Bill. They tell Bill he has that energy, that vibe, that killer instinct. Bill can become a star.

Bill learns that those labels pave a path to people willing to pay him $20,000.

What ARE those labels?

Again, it’s critical for Bill, and other success gurus, to find the right labels. The right labels lead others to believe that Bill is a success expert. Most gurus lack the professional background, professional results, and more importantly, the professional experience they claim. Bill ignores this. Or rather, Bill is not conscious of it. Instead, he fancies himself a Jeff Bezos. He believes his invite to the coveted Allen and Company meeting in Sun Valley, Idaho, is just around the corner.

Let’s unpack how the credibility labels start and work.

At the masterminds and events, Bill learned that he needs to use a device called leapfrogging. The tactic was made popular by self-development guru, Robert Ringer. Robert Ringer, best known for Winning through Intimidation, explained leapfrogging in his audio courses. Basically, instead of going through standard channels to become known, you simply call yourself an expert. Robert Ringer, I believe, intended to motivate his listeners to move past their fears. For instance, you can write a fiction book without worrying about getting a PhD in literature. The negative side, however, looms large. We find that success coaches merely label themselves as “business experts” although they have very little actual business experience. It’s like buying a black belt at a martial arts store and labeling yourself a black belt in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu.

A guru often preaches the leapfrog idea alongside rousing motivational platitudes. Tony Robbins may be the most famous person who used the leapfrog tactic (although he didn’t buy his label. Guthy-Renker paved his path). The core lesson: you are the story you tell yourself. If you don’t believe you’re an expert, you’re falling prey to a toxic mindset and playing victim to social conditioning. Tell yourself a different story. You deserve what you want. Only you can tell yourself that you’re not an expert.

Clever foxes figured out they could profit on the leapfrog. They know that someone like Bill will pay through the nose to be seen as an expert. The foxes figured out how to sell labels gurus want by selling the credibility the wannabe guru desperately desires. These foxes have created potent pitches that sell done-for-you credibility. They pitch that anyone can become a best-selling author or a recognized expert in their field. And luckily for these foxes, the labels help boost conversions on a guru’s sales page. A guru like Bill pays a few grand, and the label foxes handle the rest.

Where does this mini-industry exist? You’ll find them at larger marketing events, like Traffic and Conversion, Russell Brunson events, or other success events. For instance, if you attend a Dan Kennedy event, it’s impossible to not meet someone selling you credibility.

Here’s what I mean by credibility or labels.

- Want to be a “Best-Selling Author”? You can buy it.

- Want an article in Forbes? You can buy it.

- Want an article featured in HuffPo? You can buy it.

- Want to be on the news? You can buy it.

- Want a video reel that looks like you’re speaking to raving fans? You can buy it.

- Want some “as seen on” labels? You can buy it.

- Want a Shark Tank Host to call you an expert? You can buy it.

- Want some “featured in” labels? You can buy it.

- Want to trademark your “Highest Income Expert of the Universe” self-donned nickname? You can buy it.

Who sells them?

Almost too many companies to list, but here are a few:

- Lioncrest Publishing

- Advantage Publishing

- Speak in Dubai

- Speak at Harvard

Bill starts buying labels.

The labels aren’t cheap. But Bill depends on them.

He pays Lioncrest to do a “best seller in a box” for him. Lioncrest is one of the many publishing agencies that offer to write you a book. Then they find ways to call it a best seller, so you can use the book as a business card. Bill pays them to give him a best-seller label. Bill uses a Free Plus Shipping funnel he learns from Russell. Hint: the shipping cost pays for the book.

We’ll throw some luck Bill’s way.

The new book funnel launch does well. Bill first sells it to his affiliates in the health niche, as in, other “Bills.” Who buys? The people who command failing-to-mediocre offers. Now, you might think this would be a small market. But you’re wrong. If you look at the amount of offers on ClickBank, or the amount of people attending Traffic and Conversion—it’s significant.

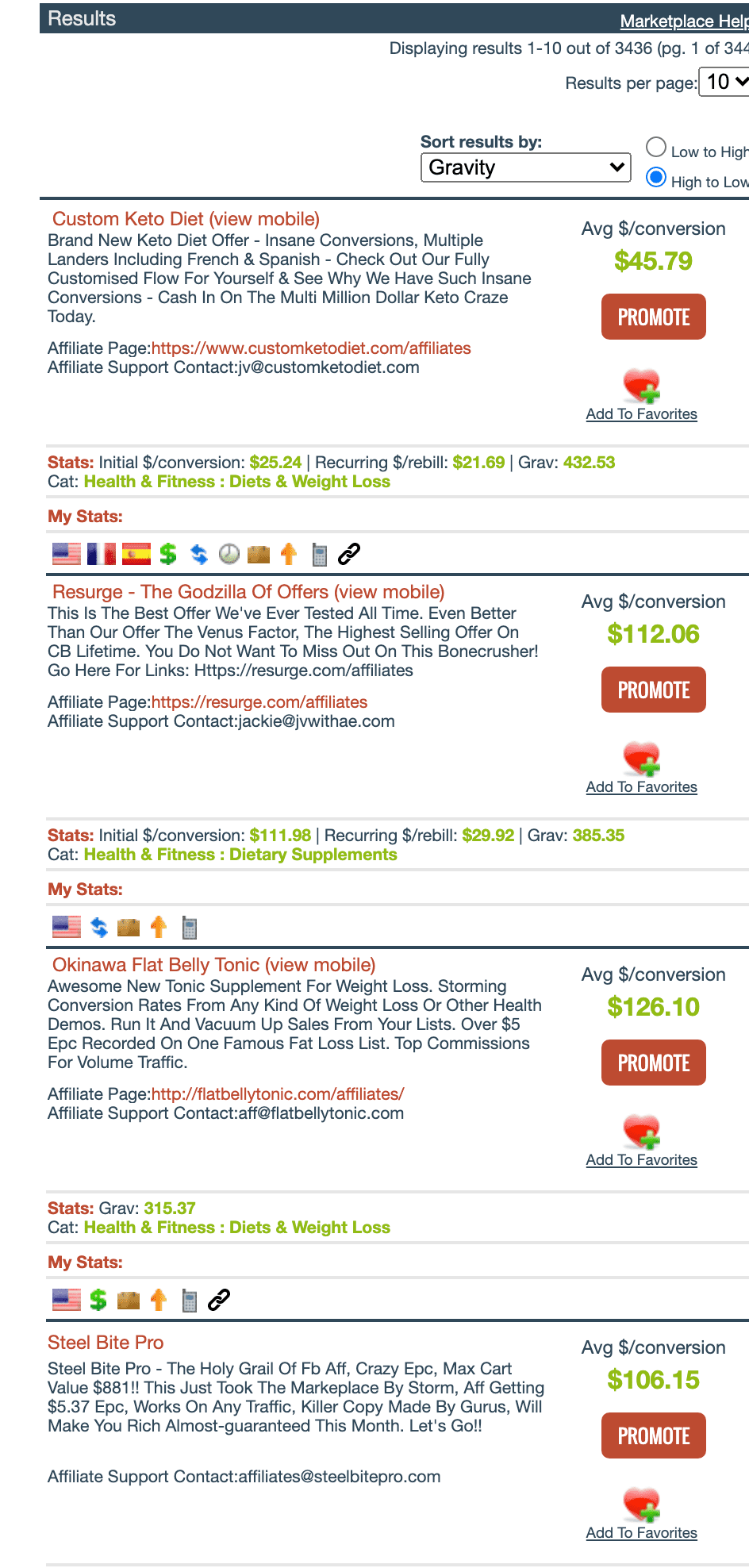

How a place like ClickBank is where Bill finds his first customers.

Take the ClickBank world for a moment. As of this writing, 3,436 products are sold on ClickBank. If you click on the Marketplace—the area where products are sold—you’ll see page one out of 344 (note: you now need to have a ClickBank account to view the Marketplace). You also see the current ranking. The top offer on page one is number one out of the 3,436 products sold on ClickBank. ClickBank lists ten offers on each subsequent page.

Page one is the holy grail. If you make it to page one, you have bragging rights. The top two can be well into producing eight-figures. But the top five offers, generally, are the only ones earning well over seven figures or more in gross profits.

After twenty, they drop off a cliff, usually into five figures and much lower. It’s here that we also find many former page one offers—offers once revered as doing it right, now at best trickling in a few hundred dollars or less each month in sales.

Basically, only .14% crank one million or more. Then a small fraction do six figures, and the rest below that. In sum, around 99% of people on ClickBank are not cranking profits. That’s a few thousand entrepreneurs. And that few thousand, not making it, are the ones who Traffic and Conversion preys on. Those are the people who pay through the nose for the masterminds. That group comprises the people who believe they can buy secrets to success. That group buys from Bill.

In case you’re wondering, Bill’s previous hit offer would likely have been number eight in rankings for a little bit. And most gurus who came from the ClickBank world were maybe on page 200 or 300, at best. That’s not to say this group doesn’t make money, but it’s a grind.

How do they make their money? How do they afford masterminds? They get quick hits of cash by selling the top ten offers to their email list. Meaning, that guru who teaches “how to write persuasive sales copy,” made money on the backs of other people’s copywriting, not their own. In other words, that guru never made their own sales. Their money came from a tested email swipe that drove clicks to a top offer.

That 99%, the ones who aren’t earning a ton on ClickBank, dream of being in the top five. The dreamers comprise Bill’s demographic audience. And this group acts as the ground where Bill first finds his footing. Eventually, as Bill buys more labels, his marketing will attract those who are unfamiliar with digital marketing. Soon, to outsiders, Bill will claim to be a guru who’s started million dollar businesses and coached top CEOs.

Bill’s rise to guru riches.

We’ll give Bill some more luck. Let’s say his new book funnel is a hit. The done-for-you book Bill bought is called Uncompromising Success. And Bill hammers the theme Uncompromising. Bill got lucky. Most gurus blindly pick a label by throwing darts, hoping for one to convert. The product stays the same, but it takes testing and time to find the right name and labels. Then, when one dart finally hits the board, gurus run with it.

Bill uses Clickfunnels pre-loaded and designed for things like a book, Free Plus Shipping funnel. Bill takes all the money from his funnel and buys every credibility label he can.

He pays “Speak at Harvard” to get the logos.

He throws money to anyone selling schemes to allow him to say he’s been “featured on.”

He buys highlight reel footage.

Lioncrest gets him some published articles.

He pays to trademark “The Greatest Income Coach Alive” and “The Result Getter.”

Bill pays an image consultant. He gets hair plugs. He grows a manicured five-o’clock shadow. He even colors his beard. He starts wearing ripped jeans, a members only leather jacket, and high tops.

Why?

He needs to mold his image to the Uncompromising theme. And the image consultant, an attractive woman, sold Bill a line. She eyed him up and down, touched his shoulder a few times and let her hand linger a little longer than normal. She laughed a little too long at his jokes. She name-dropped a few entrepreneurs she worked with. She told him that she sensed something she rarely saw in all the other men and that he packed the lone-wolf presence displayed by the character Bobby Axelrod, aka, Axe, on the television show Billions. When Bill hears this, he nearly throws his wallet at the woman making the pitch. He misses the fact that she told around fifty other guys the same thing.

Bill can’t spend the money fast enough to get the labels.

He wants to be the highly polished bad boy he envisions.

He wants to look like he’s Uncompromising.

Now when Bill buys the label, he believes he is that label—because you are the story you tell yourself. He loves telling people that he taught at Harvard Business School and blew them away.

How can he make that claim?

He bought Clint Arthur’s “Speak at Harvard” program. You don’t actually speak. You get photos where you fake speak at a Harvard approved space. Bill brags that he was prominently featured on a morning show and spoke on how to start a business during a recession. How did he do that? As part of Speak at Harvard, they promised him a morning slot on some morning show in an offbeat market. Bill also buys label packages offering “highlight reel” footage. These highlight reels show him succeeding, and he can use them on his site or on a stage.

Now, he deludes himself into thinking the folks at NBC needed him to come on and spout advice. But, in reality, Bill wants that label. He misses the fact that his chat on the morning show aired to a tiny market and that he was a mere blip. He believes he’ll be stopped in LAX and asked for an autograph. He believes, truly, that he may be invited on Shark Tank to be a guest Shark.

And that’s it.

Guru’s sales pages are full of labels. But most didn’t earn those stripes. They bought those stripes.

And those cosmetic stripes help Bill sell. They imply that Bill is a success expert. The labels and highlight reels help him check the “credibility” box he needs for conversions.

And, he gears each new label and highlight reel toward selling his mastermind.

Now, Bill needs to name his mastermind. He needs something catchy, something tied to the Uncompromising theme. He goes with, .01%ers Inner Circle.

Bill loves this.

He thinks a real life Bobby Axelrod would join something like the .01%ers Inner Circle. Bill isn’t some lowly 1%er. Bill certainly isn’t some 99%er working a nine-to-five job like some undisciplined poor loser. You know, those pathetic losers who hit their snooze buttons. Those losers who don’t even optimize their day or set goals. And Bill, well, with his new image, he’s above that. He’s a .01%er.

All the while, Bill misses the fact that he sits in the lower median end of the 1% income bracket and will never be in .01%er income. Still, his delusions of grandeur far surpass his income.

Bill’s structure for the .01%ers club.

Bill’s going to run the basic format for the .01%ers Club.

First, Bill reinvents his products.

He ties them to the Uncompromising theme.

- Uncompromising Copy

- Uncompromising Millionaire Secrets

- Uncompromising Success

- Uncompromising Instagram Influence

The lessons Bill stuffs into the course, more or less, use the “open-loop” tactic. The idea: tell just enough that you raise curiosity but don’t reveal the ending. The brain will want to “close the loop” to resolve its curiosity. This tactic proves dependable with the digital marketing community. Even the ghostwritten books now deploy it to sell more tickets to events. Bill salts his content with open loops. He insinuates that the real secrets, the most lethal success secrets, reveal themselves at the .01 %ers Inner Circle.

As Bill does this, he also pays a copywriter to work on his sales page. They throw on the labels. They use the highlight reels. And Bill pays big bucks to do a video where he’s speaking in front of a window with an ocean view. Then another video where Bill sits next to a black 1969 Dodge Charger, like the one Bobby Axelrod drives. Then another video of him on a private jet.

Bill spews his pitch. He wears jeans and a V-neck and dons a five-o’clock beard, which he colored darker. He loves his paid for “edgier” image. Bill starts claiming that he’s started many multi-million dollar businesses. That he’s grown those businesses to nine-figure empires. That his advice has helped sell over $500,000,000 of products. That he’s helped people conquer anxiety, vanquish depression, lose weight, buy their dream house, and rain blows on all excuses. And that he’s saved dying marriages (despite Bill being a virgin at 37).

Why is Bill concocting ludicrous claims?

Because his copywriter makes stretch claims.

What’s a stretch claim?

The stretch claim is a tool used by everyday marketers, aggressive snake oil salesmen, and everyone in between. The core idea: take an inane data point and make it sparkle. You take something like “two out of ten times” and say, “It peels off fat 20% faster.” Or, the copywriter could really stretch it and say, “20x faster.” How can he get away with saying 20x faster? Technically, he can’t. But if Bill gets called out on it, he says the copywriter or someone misread the information. A stretch claim isn’t always used to bullshit or lie. But as you can see, it’s vulnerable to abuse.

Another dark, yet comical, side to stretch claims: the positive-growth mindset mutated with future projections. Here’s how it works. Let’s say Bill gets a successful mastermind attendee (yes, wealthy people join; look at Tony Robbins). Now, the attendee has a health product that profits $30,000,000 a year. Bill will lay claim that his advice helped that attendee grow his business into a $30,000,000-a-year business. Despite that attendee having already succeeded well before Bill ever sold success. But Bill stretches that his advice led to those millions. He makes that stretch to sell “proof” and “credibility” that his advice works.

Another stretch. Bill attends the Dan Kennedy, Dan-Only Seminar and gets invited to dinner. To Bill’s delight, Adam Witty, the owner of Advantage Publishing, joins the group for dinner. Adam is a wildly successful entrepreneur and one of those foxes selling labels.

Bill will claim that he “helped” Adam Witty. He stretches that he helped Adam take his business into the stratosphere. He will take Adam’s profits, the profit number Dan Kennedy claimed Adam as having, and then roll it into his sales pitch. Bill may not use Adam’s name, but he will brag that he helped grow a massive publishing business to that level. That’s the stretch.

That stretch can be pushed by an aggressive copywriter, especially if the wannabe guru lacks previous results. Like Bill. The copywriter wants to get paid and wants a converting offer. If someone like Bill comes to him, the copywriter will say, “Can you reasonably say you discussed business with anyone more successful than you?” That’s the legal rhetoric. And Bill will jump and say he chatted books with Adam Witty (before Adam Witty sold Bill something). The copywriter will then cook up the claims. At other times, the guru cooks up the stretch. Regardless who cooked it, the wannabe biz whiz tricks themselves into honestly believing it.

Bill believes in his claims. Bill thinks his random conversations with people at marketing events correspond to him helping people get over $500,000,000 in sales. And Bill springs from what-if future projections when he claims that he started multiple seven-figure companies. He believes some past funnels he ran in the health niche, had he kept them going, would equate millions of dollars.

As Bill adds more credibility labels to his mastermind sales page, he pounds his list with emails. He mixes Tyler Bramlett (a popular email writer in the affiliate marketing sphere) and Russell Brunson style scripts. He emails his list five times a day, every day, month in and month out. On social media, he hammers his live coaching. He makes videos with titles like 3 Questions Every Millionaire Asks Before Going to Sleep. In those videos, Bill constantly hints or directly states that coaching is key.

Why does he say coaching is key? Because it drives sales. It’s also a mantra Bill himself believes.

And Bill sells his .01%ers Inner Circle hard.

The skeleton of Bill’s .01%ers club.

Here’s Bill’s basic .01%ers blueprint:

Cost to join: $20,000.

Bill makes you fill out an application. He only wants qualified “hustlers” because the .01%ers Inner Circle isn’t for someone not willing to do the hard work.

The application?

A sales tactic.

The idea works like an exclusive country club. You must somehow prove you belong to this group. You must somehow impress the club. And this tactic works well in this market. Why? For some people, it’s important for them to impress upon others that they belong. And this psychological insecurity runs rampant in the success world. Yet as long as you, or a power of attorney, can write a check or float a few credit card payments—you’re in. You don’t even need a heartbeat—as long as you pay. The application is aimed at someone who believes in the exclusivity of the mastermind.

Bill plans to host the .01%ers Inners Circle four times a year. Each meeting lasts for two days. He limits the mastermind to fifteen attendees and offers a one-hour hot seat. While the attendance is limited to fifteen, usually eight to twelve show up.

Bill runs a standard hot-seat style mastermind. The masterminds with over twenty attendees run more like an event. An expert will lecture, well, in reality, pitch for an entire day. These masterminds tend to feature generic names like “Discovery Day” or “Day With So and So” or “Summit XYZ.”

Bill also promises that guest experts will come and speak. At first, Bill pays a guest expert to show up. It’s easy money for the expert. You get your travel paid for, and you don’t need to do any prep. Essentially, you get a paid weekend trip. As Bill develops, he can then charge guests to attend, or he can cut a deal if the guest expert makes any sales at the mastermind.

We’ll strike some more fortune to Bill.

In a year, Bill gets twenty people to join .01%ers. He’s ecstatic. He earned $400,000. Now, Bill ignores the fact that he spent most of that money on credibility labels and highlight reel footage. Like most “experts,” he focuses on profits. That money spent, to a guru, equals an investment that will deliver wild returns in the future.

Still, Bill deserves credit. Often it takes a few years to get this many people to join. Bill hustled after he left the health niche, and he hustled his way to get twenty people to join .01%ers. And he sold his Uncompromising products. We’ll say Bill did well and sold around $100,000 or so. Again, kudos to Bill. Selling this many info products and grossing this amount inside a year is not easy. In fact, it’s not very likely, but for our sake, we’ll say Bill’s converting.

Let’s take it back to Bill’s .01%ers Inner Circle.

Bill might ignore this, but in running a mastermind, truly, we find few overhead expenses. Let’s walk out the costs.

- Conference Room: Average Cost $70–$160 an hour. Bill books a room in San Diego for $100 an hour for two days. Total = $1,200.

- Bill gets a projector for the room for two days. Total = $200.

- Bill wonders on food. He could pay for some coffee and fruit for an additional $200 or he could go on the cheap. With the common cheap route, the guru flies in the day before, runs to a Rite Aid, and buys two boxes of Kind Bars. Then he gathers as many free bottles of water as he can from the hotel and the Uber driver. Bill goes the cheap route. He buys two boxes of Kind Bars. Total = $24.

- Bill books a first class ticket (what happened to that private jet?) for his Instagram selfie. Total = $1,200.

- He books a hotel room for three nights, roughly $400 a night plus the taxes and hotel fees. Total = $1,500

- Bill declares separate checks for dinner. But we’ll say an attractive attendee, Amber, joined the mastermind. Bill buys $100 in drinks one night, but only for he and Amber. He cleverly ducks buying drinks for other attendees. Bill doesn’t tip—despite his social media claims that he loves giving huge tips because he provides so much value to people. Bill gets angry when Amber heads to another bar with a fitter, taller guy. Total = $200

- Bill hires one guest expert, a copywriter, to come to the event. Total =$3,000. The role of the guest expert: usually to show up. Also, and often, to come in and pitch their services or their mastermind. They may have a prepared talk, but that’s usually for something with more than 20 attendees. The guest expert is often someone known in DR. It could be a media buyer, a copywriter, an email expert, and so on. The guest expert is just a selling point.

Now let’s look at this from the attendee perspective. The attendee is going to a meeting where Bill earns $100,000 to just show up. Minus the above costs, Bill walks into a room for $92,676.00

For that amount, what does Bill offer?

We know he bought his credentials. We know he basically knows sales funnels that sell chintzy info products. We know he hasn’t really started multiple seven-figure businesses. But to most attendees in the mastermind world, fact-checking the claims or Bill’s background is “toxic thinking.” It’s a “victim mindset” and not a “growth mindset.” Most never question the labels and the claims.

Why? Numerous reasons, but a big draw to attend is the status of joining. The mastermind signals status, peacocking how the person “hustles.” They also get new bragging rights to drop at the next internet marketing event. Another reason is that people mistake the cosmetic busyness of a mastermind as doing the real work.

Now, back to Bill’s keen business insights.

What does Bill offer?

Not much.

Bill’s going to repeat things like “what I learned from successful millionaires.” He’s going to offer goal-setting secrets or ideas he hunted from books. Bill teaches what most gurus teach. Bill spouts clichéd sales sayings like “everything is marketing.” He’ll say buzzwords he learned from a buzzword bible like Simon Sinek’s Start with Why. He’ll offer some sayings he heard on Shark Tank or The Profit. Bill believes those shows resemble real business dealings. (They’re as close to real business dealings as he’ll ever get).

I’ll take the reins here.

Let me guide you from my experience.

I attended dozens of different masterminds. I paid to join masterminds, and I was paid to be the guest expert. I was deep inside this world. I sipped the Kool-Aid. And by all accounts, my copy results made me a “star.” I was in it deep for about eight years before I came to my senses. While these examples are based on my experience, I doubt my experience would be far outside the norm for most masterminds.

Let’s zoom back into Bill’s mastermind one more time.

First, we meet the attendees. Bill gets the usual attendee mix you find at almost every mastermind. I’ve rarely seen anything different than below. It gets to the point where you can spot who’s who when you walk into the room.

Ten people show up to Bill’s .01%ers Inner Circle at the Hard Rock in San Diego.

- Diet/life-hack person

- A copywriter (not the guest expert) who wants to start his own business

- Person clinging to online direct marketing circa 2008

- Guy or gal with business partner issues

- Another Bill who just hit a big offer or their offer is now foundering

- Someone claiming to be the guest expert in a one-upping contest with the actual guest expert; both act above everyone else

- The “wow this is a firehose of information!” person

- Someone banned on Google, Facebook, Amazon, Reddit, 4Chan, and the dark web

- Creepy sex guy or someone incredibly overbearing

- Nervous direct marketing outsider with a real business

Once everyone sits, Bill reviews the standard mastermind rules. Bill explains that each person gets a one-hour hot seat. He says anything said must be tested and proven. That means that theories, post hoc rationalization, bragging, boasting, platitudes, and wild-eyed ideas rooted to no reality are about to begin.

Regardless of who goes first, the meeting goes off the rails.

Well, off the rails to an outsider; to someone attending—the ideas seem to be cooking.

Everyone starts talking at once.

As soon as some inane PG sexual comment is made, the creepy sex guy is off to the races about his seventh Thai wife and how she’s submissive to his spiritual masculinity traditions. And he goes on and on about his own “orgasm” orgies. He says the word “labia” way too many times.

The diet hack person tells the fittest person in the room that what the fit person eats is unhealthy. The diet hack person also can’t wait for dinner. Why? They love to bring their own bag of food and tell everyone in earshot about their diet (they had a different diet at the last mastermind).

The 2008 guy is shocked that no one wants to pay $4,997 to join his forum coaching program. And he bitches that Clickfunnels, while insanely easier, isn’t necessarily better than his complicated set up for WordPress (or it’s a male seduction niche person still clueless as to why their entire niche went bust soon after Trump got elected).

Then someone puts up a sales page. The guest expert copywriter either calls it shit (it usually is shit), or he says, “You need a bigger more aggressive hook.” Then people bandy about crazy hooks. The nervous outsider will ask, “Is it even legal to say that?” That gets shot down with Bill saying, “The product graveyard is filled with great products that were never marketed!”

The stuck-in-2008 guy starts some copy theories. Soon, 2008 and the guest expert copywriter battle for the craziest hook. Bill gets in on the game by bragging about his mindset while writing his one hit letter. He gets passed over, again.

Bill glares at the guest expert copywriter.

The copywriter, to Bill’s dismay, misses Bill’s glare and goes even more aggressive with copy hooks. Soon, who knows what the hook means or how it relates to the product, but it’s out there. It involves a government conspiracy, aliens, Nazis, two hours of sexual stamina, Hillary Clinton, who really killed JFK, and one lost ancient 2,000-year-old Chinese secret somehow unearthed—all for selling a new greens supplement.

Then the new Bill gets up. We’ll say this Bill’s hit letter has now turned to its downward spiral. Since the copy once performed, the usual theories come up. Test a different button color. Test a new headline. Test a VSL Tower. Test a new voice over. Test $47 instead of $37. The new Bill will try all of these tiny changes. He believes they will revolutionize his sales page. Yes, he, like other attendees, believes changing the button color will somehow turn sales around for good. In about two masterminds, the new Bill will announce his shift into selling success.

Then the first break. The firehose-of-information guy heads to the bathroom. At the urinal, he tells everyone how “knowledge bombs are being thrown. It’s just a firehose of information! I can’t wait to go back and apply all this insight!” He will go on to say that again and again. And, again. He’ll also tell the hostess at dinner why she should join a mastermind and that coaching means success and that not going is an excuse and accepting failure in life.

With each subsequent hot seat, the one-upping, the posturing, and peacocking soars. It becomes a social theater. Even at events where the expert is presenting and the attendees are asking questions, we mainly find a buzzword pitchfest.

No matter which type of mastermind, the people attending offer a bloggable glimpse into their psychology.

On one side, we find awkward social theater. How so? One person always asks, “I’m willing to do whatever you tell me. Where should I start?” It’s an awkward, cultish question. But the person asking, likely, doesn’t worship the guru. It’s generally asked to signal that they will do whatever it takes to become a success in front of everyone else.

And in the same vein, we find pseudo-vulnerability statements or questions. Someone gets up and makes a “personal” statement. This person attributes a massive life-change to the guru. Like, how they just started to lose weight. And they know that, in a year, they will lose 100 more pounds due to the guru’s lessons (in a year, this person still struggles to lose weight). Again, more cult-like behavior, but it all generally signals something.

What’s hip now are edgy guru responses deemed “tough-talk.” But this is wildly narcissistic and demoralizing. Basically, when someone asks their question, they are met with “you’re a fucking loser driven by your excuses.” You’d think people wouldn’t want to ask questions like this to a guru with a colored five-o’clock shadow who will call them a fucking loser. But this environment proves rife to signal and posture for attention. Someone wants to get up and appear as if, “I’m willing to do what it takes, even if it calls out my bullshit.” It’s theater.

Last, someone gets up to moralize that they were once riddled with excuses and their life was in shambles. Then something the guru said turned it all around. It’s a come-up-to-the-microphone-and-one-up-the-room drama.

I’m sure these people mean well. But they miss how sad they’re acting. They also mistake the theater as “digging in and doing the work.”

The only advice we find is growth themed. We can draw out some tangible advice, like some tech or IP updates, and arguably tangible strategies, like basic goal-setting and scheduling your day—all things that you can find in the business section at an airport bookstore (and likely where the guru found them).

Bill hosts his .01%ers mastermind four times a year. Old attendees will drop in, and new ones will join. It basically repeats the above. Now, Bill could keep just that mastermind, but he will be sold, by Russell Brunson and other foxes, that he must sell other events. And Bill will do just that.

Bill, wisely, leverages his mastermind as a way to get comfortable with public speaking and to sell “how to be a high ticket closer” themed products and events. As Bill gets better with his pitch and buys more labels, he may straight sell his mastermind at events. He will speak at other masterminds to sell his mastermind. Like many gurus, the mastermind provides Bill a key tool to his business. As long as Bill keeps at it and some luck favors him (he needs luck because he doesn’t carry the weight a name like John Carlton does), Bill can profit a decent six figures a year from running his masterminds.

Let’s zoom out of Bill’s room.

Let’s look into the unspoken nature of a mastermind.

First, let’s take a gander at the advice.

The mastermind is sold as “next-level” advice—advice so powerful, it’s often considered a secret, a proven strategy, a no-nonsense way to grow your business and personal income. Heck, even marriages claim to have been saved. Also we see it billed with “high-level” connections and networking. As in, you pay to plug yourself into some money-making, self-growth Illuminati.

That promise land?

It always has been, and continues to be, a mirage painted by copywriters. That “next-level” advice has never been tested, backed up, or fact-checked. It’s a massive marketing promise. That promise adheres to narratives people tend to accept as the right way. For instance, as billed on the sales page—or the guru’s relentless repeating on Instagram—it’s all about growth and why coaching is so critical to get growth. You’ll hear sayings like:

- If you’re not growing, your dying!

- Scale your business!

- 10x, 20x, or 30x growth!

- Crush your conversions!

- Build your list!

- Get one million followers!

- Grow your income!

- Triple your revenue!

This all comes from a shopworn map.

The entire pitch aims at selling business growth. And it states that you can’t crank revenue without increasing your conversions. Meaning, this growth advice ties solely to conversion-based growth, not customer-based growth. 2

That plays out with “focus on revenue.” Or in the digital marketing world, focus on things seemingly tied to increasing conversions: headlines, copy, email marketing, funnels, buying credibility labels, daily email marketing, affiliate marketing, social media marketing—anything tied to selling. All of it is tied to increasing conversions to increase revenue.

Revenue matters. I’m not against revenue. Making revenue, attaining success, sharpening skills to capitalize on luck to strike while the iron is hot, matters. Conversions matter. A great product deserves marketing that converts.

What’s wrong with this advice?

“Grow revenue” is the easiest advice to give.3 And most “business experts” only cosmetically know the advice. They bought into it at face value. They never question it. They miss that it says the same thing as the last book they read. Or the last event they attended. Gurus love things that promise growth. They scramble onto YouTube and offer “7 Secrets to Become a Millionaire,” and all the tips—along with constant name-dropping—tend to be goal-setting claptrap or old sales chestnuts about growing.

The advice feels right.

It sounds right.

It’s motivating.

It sounds like winning.

That’s the thing—it’s easy to valorize “growth” advice. We see it as winning. We see growing revenue as a scoreboard. And obviously we want to do well. But we fetishize the result and miss the process. It’s like working out. We want to look svelte, shredded, and muscular now! Well, we can’t skip the process. Yet in business, just like getting a fit body, we’re sold that we can skip the process. And even when a top CEO or billionaire answers the what-does-it-take-to-make-it questions, they answer with clichés. In other words, it sounds like an coach after a big win, “Well I trusted these guys; we worked hard all week.” It’s the easiest thing to say. And it sounds right. But many gurus and their customers only go for that sugar high.

The growth advice distracts from reality. It distracts from mundane details, luck, talent, experimenting, failure, and arduous work.

Now, you can make money this way. Bill makes money. Frank Kern makes a fortune from slinging marketing growth. But the unseen issue is that, like most success gurus, you must attain hit product launches delivering windfalls of cash. And those are rare. Plus, by neglecting to spend time in research and development, the product turns perishable.4 The cash dwindles. Soon, you end up chasing new tactics to rekindle revenue. It’s a constant hamster wheel of running after profits, hunting new tactics, and chasing more revenue.

Software pioneer and Silicon Valley Software entrepreneur, Daniel Gross, explains why “growth” advice sounds right, but it’s often the wrong advice. Gross poignantly states, “Growing revenue is the easiest advice to give, not the best advice to give. What you really want is to make the most desired product as quickly as possible. By chasing breadcrumbs of revenue in the short term, you can distract yourself from building something really great in the long term.”5

I couldn’t agree more.

Yet in the digital marketing world, marketing advice world, and business success world, all of the lessons focus on those revenue breadcrumbs. The closest we get is to “find your customers’ pain points and then create a product that solves it.” That advice sounds right. But the deliverables are created with sales-page logic and lack an obsession to create a great product. The advice tells you not to follow Halo Top’s two intense years to make their flavors, not good enough, but perfect. Halo Top created a low-calorie ice cream. They practically ignored marketing and focused solely on creating a great product. They broke almost every rule taught by copywriters, sales trainers, and marketing experts. By focusing on product versus marketing, Halo Top became one of the top three selling ice creams in North America before being bought by Wells Enterprises in 2019 (it sits in second place currently).

Whereas in a large corner of digital marketing world, the method is reversed. Gurus and companies simply create something for a product launch.

The result? A chintzy product.

And constant focus on growth weakens their business.

Why?

It entraps them in chasing quick sugar high hits of revenue.

Gurus spout growth advice as if it’s a universal truth. They say it with such conviction that it sounds more true than the law of gravity.

Why?

Why such belief?

Why such repetition of growth?

Two reasons.

Primo, bigger players like Gary Vaynerchuck or Ryan Deiss know that growth advice sells. They also know it entertains. They shape and craft a stage persona that best sells this shtick. For instance, Ryan Deiss crafted a polished, friendly, and dorky persona. He does this to make it look like he’s an honest marketer who likes helping businesses. Or consider Russell Brunson. He uses self-deprecation, nerdiness, and humor. Others try an edgy tough-talk persona.

Most gurus craft calculated stage personae. Many get constant coaching on the persona. And sometimes they (usually prop gurus or entertainers like Lewis Howes or Tony Robbins) get claptrap from their teams. As in, an entire team feeds them the formula, and they get out on stage and deliver it. It’s all part of the persona.

And they know they need to give easy and motivating advice. Why? It sells the dream and makes sales.

No doubt, speaking on stage or being the personality helps them get their steps down. Not many can get on stage and just wing it, and they don’t want to bore the audience either. So gurus are doing the right thing by learning how to be a better presenter, whether in a large room or a mastermind.

But with most gurus, the persona quickly becomes the only thing they know. Many believe they are the persona. They posture as someone who lacks insecurities, except forced pseudo-vulnerability displays. The guru took that “vulnerability” from their selling playbook. It looks like a hero’s journey, “Hey, I was nothing. I faced difficulties, and I still struggle sometimes. But if I can do it, you can too!” It’s meant to build believability in their product. Again, it delivers the audience a sugar high and hyper-focuses on conversions.

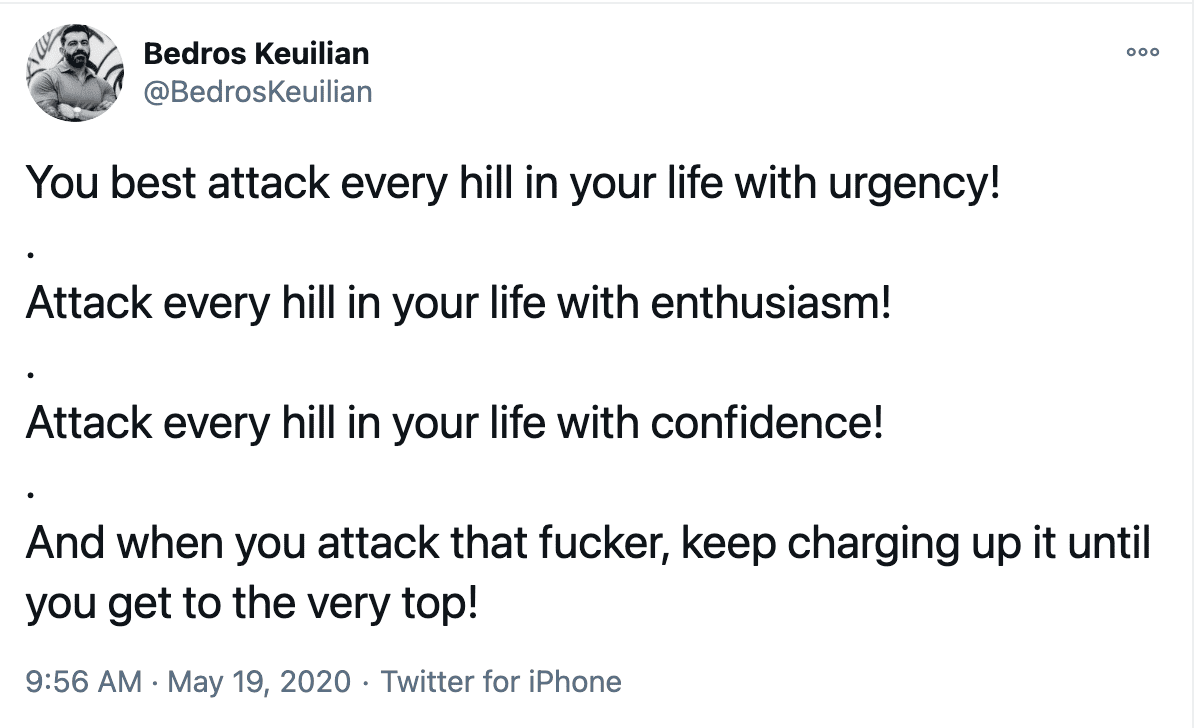

Lower level gurus like Bedros Keuilian, Dan Lok, or Jeremy Haynes sadly live on these placebo motivational sayings. They sell the sugar highs, and they use those claptrap sayings as their moral philosophy. It’s their religion. It provides their guiding principles. It’s also as far as they can think. When you see Bedros post on Twitter…

…you see the limit of his depth. That’s as far as Bedros can think. It’s as original as he can get.

That tweet shows the extent of what most gurus know. They make millionaires and billionaires into unicorn beings who never once hit a snooze button and are constantly dominating their day.

It’s a distraction.

Most “business experts” sell distraction. They sell pseudo-work. Even gurus misunderstand the advice they give. And they anxiously focus too much on the habits, routines, and buzzwords.

Why?

They too believe that the wealthy focus on those things. And they think these rigid routines provide a personal life philosophy. But they miss the fact that constantly focusing on morning routines and conversion-based tactics cripples their personal agency. Most gurus lack the erudition, insight, integrity, humility, and most of all, street smarts to recognize the flimsiness behind the advice. Gurus also live off of the sugar-high sayings.

Here’s what gurus, and those who buy into their lessons, miss: it’s just a constant narrative fallacy. They think some rigid routine is the reason for success. They buy into the secrets. They mistake the secrets as the work. It’s all these guys know.

Again, they believe that millionaires or billionaires live as unicorn beings. And if they too can get that secret, they can be a unicorn being. It’s why many gurus and people who pay Tony Robbins hundreds of thousands of dollars are incredibly anxious people. It’s much easier to distract themselves by buying another mastermind than to ponder a product or method that pioneers something. It’s avoiding work. And they lack a pioneering spirit because they handed over personal agency. Instead of facing a task, they think they need another weekend mastermind to dial in their goals.

The mastermind roots itself to the sugar-high growth-based advice. I argue that because of the status-posturing and social theater that makes up these meetings, the growth-themed advice offers attendees the easiest information to give without sounding wrong and the easiest way to sound smart.

Why do growth-themed masterminds prove useless?

Let’s dig into why the extreme ends of this advice live in masterminds and then show why the advice proves useless.

We valorize winners. We valorize success. We like results. We know a result tends to come from effort. But we over-focus on the win. If we see someone winning a ton—in a profession, sports, or elsewhere—we like to know why. We want to understand, learn, or capture the secret.

Humans are pattern seeking machines. This helps us survive. Yet we often focus too much on possible reasons and causes:

- It’s because of the routine!

- It’s because all marketing is good marketing!

- It’s because he has discipline, and he gets discipline by waking up early!

- It’s because a positive mindset leads to success!

We look to the cause. What caused her success? What caused that sales letter to convert? What caused them to become a billionaire? We start seeking those causes.

We want the secret cause. We want to optimize that cause. Maybe it was goal-setting. Maybe it was hand-copying 1,000 sales letters. Maybe it was 10,000 hours of studying marketing books. Maybe it was because they woke up early, meditated, cold-showered, set goals, journaled, and believed in themselves!

The more we look for these causes, the more we fall prey to what’s called: The Narrative Fallacy. As defined by Nassim Taleb, it’s our need to fit a story or pattern to a series of connected or disconnected facts.7

I think it also ties to Taleb’s Narrative Discipline: the discipline that consists in fitting a well-sounding story to the past, which is opposed to experimental discipline. Experimental discipline encompasses trial and error. Often, there is no playbook here. Sure, some guidelines work, but this is really about trying new things and gathering data. This is done from small personal levels to big corporate levels. Maybe you get mentored, but most of what you do is on your own. As in, you discover your secrets.

In the success selling world, most people focus on Narrative Discipline. Instead of taking a risk on something and testing it to see if it works, people look at the result and try to create a story to explain the cause.

With marketing and growing revenue, it’s easy for a marketing nerd to theorize what caused the sales. We think it’s the headline. We think it’s the funnel. We think it’s the copy. We think it’s the hook. We then go further and say things like “everything is marketing.” Or “The product graveyard is filled with great products that were never marketed.”

Where, by the way, is this product graveyard? Can anyone empirically show it to me? I mean, it sounds like all it needs is for that incredible marketer to go to this graveyard, grab a great product, and sell it. It’s a literal goldmine.

Before I lose track, let’s return to the Narrative Fallacy.

With business success and personal success, we like reasons. We want the secrets. We want to know what caused that success or that personal shift. We think it’s the positive mindset. We think it’s reading hacks to hunt “core” ideas that will boost our business. We think it’s information, knowledge, goal-setting, or routine. We want to capture the secret and see how we do using it.

If we hunt causes, we see sequences.

For instance, we think a certain morning routine can be attributed to someone’s success. We see a sequence. A caused B. Or B caused A. But often, we postulate theories as to why A caused B. We believe that sequence somehow fueled the result. When, truly, we don’t know if A actually caused B. Maybe it helped, but we don’t really know. This is called epiphenomena. We look for particular causes, and we may actually be missing the bigger picture. Gurus bet on you missing the bigger picture.

For instance, hand-copying famous sales letters offers a sound exercise to learn how to write copy. It helps practice a particular skill. It can help you recall various phrases. I myself hand-copied sales letters daily, without a missing a day, for over six years. But does it make you into a great copywriter? Who knows? In a way, it makes you an apprentice to the great copywriters. But it’s an exercise. It’s not the sole reason. In my experience, the best copywriters had belly-to-belly sales experience. They sold in person, and they were pretty good at it. It’s possible that, by hand-copying sales letters, they learned how to get their belly-to-belly experience on paper. But Claude Hopkins never hand-copied famous sales letters. Neither did other greats. Some did; some didn’t. It’s an exercise, not a reason for success.

In masterminds, the attendees tend to be a group who hyper-focus on causes. Again, these causes are seen as reasons for success. For example, let’s say someone in a mastermind is playing some beach volleyball. A mastermind person will look up “Gabrielle Reece’s pre-game Volleyball Diet from 1999.” They think this will help them, when they truly have no idea. They would learn more by playing, not looking up some obscure secret. Gabrielle Reece’s diet may have helped her, but it wasn’t her reason for success. Masterminds, and the success world, tend to hyper-focus on reasons rather than actions.

Mastermind attendees also mistake the mastermind-busyness as a path to success. Consider how the room is made up of self-interested people. An attendee may want something specific from the mastermind, but they go into a room full of people who are completely oblivious to their business. The ideas shared are often un-applicable, or they would take months, or even years, to implement. And the theories are tied to growth-based advice.

Last, masterminds display an extreme social theater. We see all types of status-posturing, peacocking, and one-upmanship. Inside the room, many think they’re getting a firehose of information. Though these are just theories; they’re not tied directly to your work. And they give growth-based advice that anyone can say about anything. Sure, an attendee may get an idea or two. But paying that amount of money, traveling, taking that amount of time away from your business—is one big distraction.

What about those big ideas that are being thrown around? Don’t they boost success?

We have zero empirical data to validate whether a mastermind fuels success. The one positive aspect lies in the people who attend. Despite paying for a distraction, they are driven to succeed. They will keep testing, marketing, and trying things. Naturally, out of that group, a few people will succeed. Let’s not forget, they could afford to join. But they found a level of success before the mastermind, and they will keep swinging at triumph.