We often hear:

“Read the other side! This way you can be informed!”

“Make sure to read both sides!”

But these statements display lazy scheming. Part of the scheming, it’s said as a virtue signal, a signal that the opinion uttered comes from a self-anointed high ground. A high ground of my opinion is correct and virtuous and since I claim to read both sides, the most sensible and virtuous people would come to find my opinion as the only true opinion. “Read the other side!” types are one-sided readers. They only read their side since they see their side as correct and true. They themselves can’t convince you to their side, nor do they know how to convince you, so they expect this one book to shatter your worldview.1 And when they deploy this “read this book” argument tactic, they never mention any substance of the book, or what the book covers other than maybe a flap summary, but, instead, recommend a book as a counter to your argument. While the book might be great — often it’s not, often it’s generic agitprop — the person throws a lazy argument, rather, a thought-terminating cliche2, of read this book to get convinced. Again, it comes down to a low-informed person who views their side as “right” and if you’re not on their side, you’re biased and “uninformed.” By the way, calling someone’s view “biased” is a bias.

Reading books of different views isn’t the worst idea, yet we’re not going to do that if someone outright dismisses our beliefs, (excuse me, our confirmation biases that cause us to play mental gymnastics to rationalize our stunted worldview) and then recommends that vapid Michelle Obama book to see the truth. That never happens. Curiosity leads us down the path, and if we’re deliberate with our curiosity, it does a much better job than some self-flagellating exercise someone wishes us to endure. I’ll share a personal example of reading the “other side” and reading “my side.”

I went from Catholic to smug Atheist to a Deist, to dare I say, a Christian deist. I can already hear someone saying, “But have you read Richard Dawkins!?”

Yes.

I have.

I turned atheist after my dad died. The priest at my dad’s Catholic parish hit me up for a cool $500,000, saying a donation like that would ensure my dad getting into heaven. I walked out to my car, stunned, and declared myself an atheist. But after a few years of holding this belief, I wanted to find out more. After all, it came from a reaction. Around 2018 or so I dug more into it. I was deep into Stoic philosophy at the time and I had attended Stoicon in London. At that event, a vigorous and rather heated debate struck up regarding Stoicism’s relationship to God. A few gentlemen castigated Stoic popularizers like Massimo Pigliucci and Ryan Holiday for turning Stoicism into a secular, atheistic humanism. What struck me, the atheist counters against the one god-fearing gentleman came in euphemisms, tropes, and what sounded like a sales pitch for a transhumanist Yoga retreat (the atheist failed the Socratic method, abysmally, and the Stoics loved Socrates). And the god-fearing gentleman fired back with poignant insight and deep knowledge of Stoicism. I kept my observations to myself, but I began questioning my atheism.

A few months later, I read Richard Dawkins, Yuval Noah Harari, Daniel Dennett, and A.C. Grayling. The more I read, the more word games they seemed to play, and the tone and prose they deployed came across as self-indulgent and smug. For instance, many thought-leader atheists imply those who have faith play word games to delude themselves into believing in a greater being. These famed atheists argue against these word games, yet then try clever “gotcha” questions, and then drone on teaching the science of evolution. But what they can’t prove in their hundreds of pages, and their clever “gotcha” questions, is that a God doesn’t exist. I noticed the more I read atheist arguments and thinkers, the more I was pushed toward believing in a being. Daniel Dennett’s take on why we have emotions, why we recognize beauty, or good and evil, to me, came across as dogmatically smug. Then on one of my favorite podcasts, The Panpsycast, I heard a compelling pantheist (pantheism, in a way too quick summary that misses much — God is the universe and exists in everything in some way) argument. It swayed my curiosity. So I looked at the arguments of those with faith. The Panpsycast also interviewed other famous theologians like William Lane Craig, and the arguments were clearer to me and less smug. And when I read Aristotle, C.S. Lewis, and the Stoics, it moved me into the deist camp. And my reverence for Christianity and my move towards Christian deism? Reading Edmund Burke and, again C.S. Lewis.

So much for “reading the other side.”

Now onto “reading my side.”

Around the time I began my atheist deep dive, I got curious to look into my political worldviews. I loosely figured I was a Conservative/Classical Liberal, and I even wore the hat, “Libertarian” for a while. But I never really looked into it with any depth. I decided to go with some left-wing views first. I read old and new, Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Kate Manne, Marianna Mazzucato, Ibram X. Kendi, and Rutger Bregman; and bits and pieces of Karl Marx, Michel Foucault, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau; and a few others escaping me at the moment (and somehow escaping me on my bookshelf). While some of it read interesting, nothing clicked with me. I found many of the arguments built on grand, top-down designed solutions; built on nihilism, and moral relativism; and built on, finally, way too much trust in the capacity of humans and societies to begin anew.

Around the summer of 2020, I dug into the Conservative side. Edmund Burke, I found mind-blowing. Thomas Sowell raised the hair on my arms (and became my hero). And modern thinkers like Charles Cooke, Victor Davis Hanson, Shelby Steele, Niall Ferguson, Madeleine Kearns, and Amity Shlaes knocked my socks off. And it resonated enough that I looked more into their influences, like Adam Smith, Alexander Hamilton, the Federalist Papers, and so on. So here, you could say I found my political worldviews, but rather, it grounded my sense of self. And following my curiosity on my worldview colored my world. That, I didn’t expect. Through these thinkers and authors, I found all types of literature, art, music, and so on (the saying that Conservatives hate art due to the bottom line is a myth). And I found out why I liked Aristotle over Plato. Call this a bias, but many principled Conservatives or Classical Liberals (if you want to get dorky on definitions) consider Aristotle their philosophical father, whereas Liberals consider Plato their philosophical father. I think that’s pretty cool. And when you know a bit of both, and see the current arguments of today, you can see both at play. But, again, my worldview got grounding and a framework.

I share this personal example not as a repudiation of atheism, nor as a repudiation of Democrats. I share this as an example of letting your curiosities guide you, and how curiosities can lead to big shifts. And these personal shifts can occur in a variety of topics. You can do this on marketing, guilty pleasure fiction, history, and so on.

Let your curiosities guide you.

Onto the haul.

Haul

A big one, and one where I have read a few books. So let’s go.

Read

As I said in the last haul, I’m doing these hauls a little differently. And sadly, due to the nature of the books I read, I wish I could devote more time to each, but I’ll do my best to keep it short.

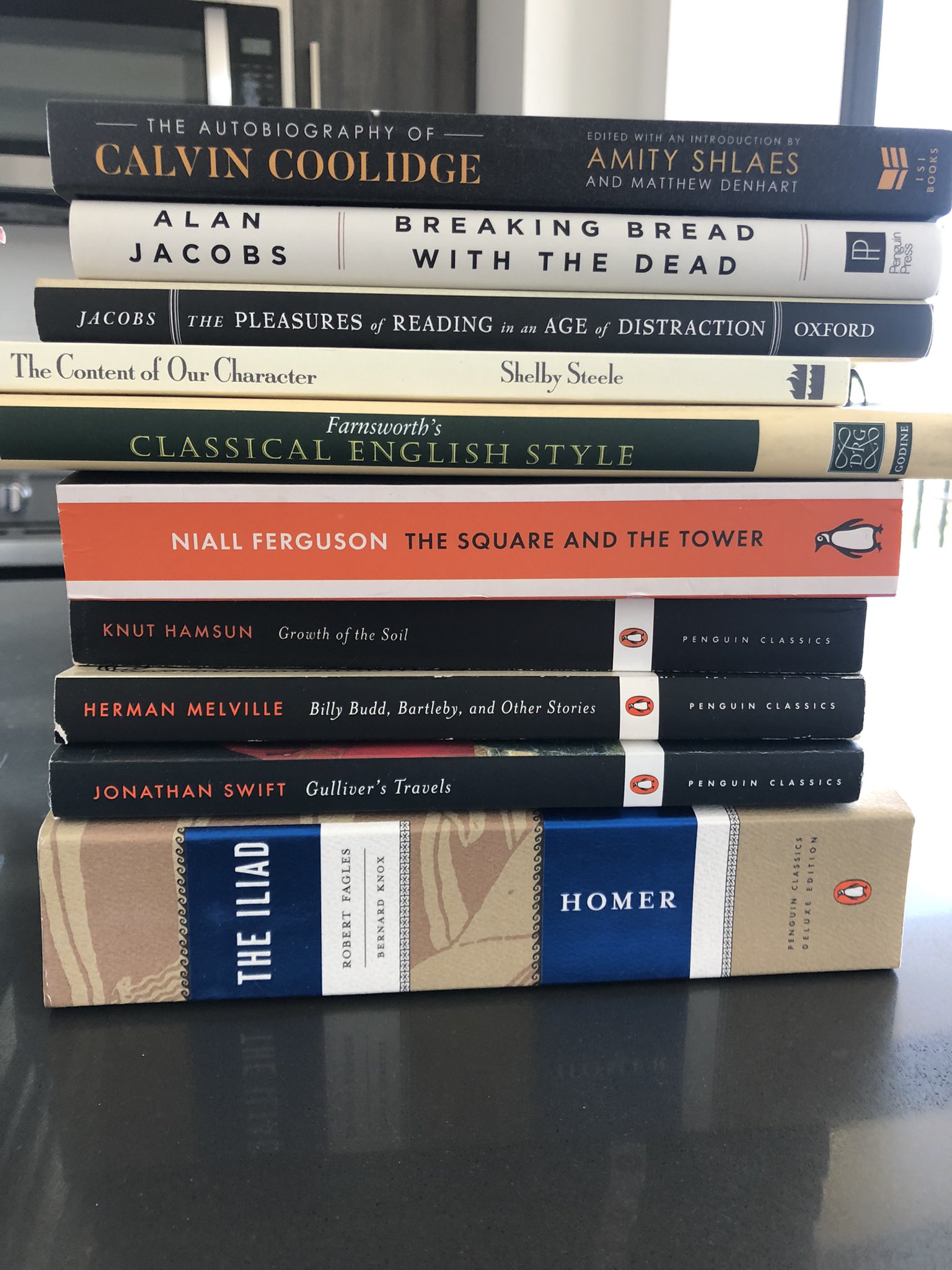

The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction, Alan Jacobs

The quick review: it altered my view on reading. It struck a chord and altered how I read, and now I wish I read this a while ago. Here are two key changes:

-

I’m slowing down my non-fiction reading.

-

I’m now reading my non-fiction with a pencil and making marginalia, mainly I ask questions (I previously used a pencil and made marginalia only if I read it a second time).

My upcoming reading course will center around Jacob’s book and How To Read a Book by Mortimer Adler, and Reading Like a Writer by Francine Prose (as well as my own beliefs and experience).

I’m a Mortimer Adler fan. His book How To Read a Book I could call a “life-changer.” If you know me, or if you’re a Good Word member, Adler’s methods root much of my reading style. Adler didn’t just write a book on reading, he was a formidable mind, a mind and figure influencing our current world. He’s also the master curator, or the OG as the kids say, of The Great Books. It goes without saying Adler is worth reading.

I love Adler, but Adler was a snoot. I admire his snootiness, it relates to judgmental and stubborn tendencies, but Adler sees reading for pleasure as pointless. Jacobs quickly points out the fault in Adler’s position, and Jacobs is right. I like to think Adler truly loved the Great Books and found immense pleasure and purpose reading them, which is easy to do, but I’ve argued elsewhere that Adler was a gifted and professional reader, and his advice comes from a rare mountaintop. And his issue, he teaches his advice as if most readers are his equals. Most readers are not Adler’s equals, some climb the mountain to sit next to him, but no one starts off as Adler’s reading ability equal. Jacobs puts into words the merits of Adler, but also the issue with Adler, and that is, getting into reading, and taking out the dogma. Jacobs offers a far more approachable way to read books, and not only more approachable, a far more enjoyable way to get into reading, to make the most of reading, and to better understand the kinds of books Adler heralds.

Jacobs also recognizes something Adler misses, reading speed. Today readers are hounded to read faster. But trying to read faster, as galaxies of evidence reveal, destroys comprehension. It also destroys the ability to enjoy a book, to enjoy sentences, to enjoy the story, and, most important, destroys the ability to engage with the book. Also, reading speed is genetic. I know some people that inhale books at an incredible pace. I know some people who read incredibly slowly. Jacobs argues to work with what you have and to slow your reading down enough to read at a pace allowing you to engage with the book on your terms.

But one of the best lessons from Jacobs, tapping into your pleasure and curiosity to foster a better reading habit. Jacobs shows the flaws in “reading lists.” He introduces the idea that many reading lists today appeal to those who want to “have read” versus reading. For instance, the standard “read these nine books before you die” fare. Most of these lists fall for the correlation does not imply causation fallacy. Simply, having read Psychology of Money, Atomic Habits, Sapiens, How To Win Friends and Influence People, Alchemist will not make you more successful, wealthier, smarter, a better salesperson, or any other trite promises attached. And Jacobs goes further to show that while reading has benefits, having read say, Don Quixote does not automatically make you a better person. Jacobs kneecaps the lists saying “read only these books.” He shows how that’s constraining and sucks the pleasure out of reading, and most important sucks you out of reading.

Jacobs offers a balance. He offers a way to find better books, read better books, and how to read books better. He calls it swimming upstream. Which is, if you love an author, fiction or non-fiction, see who influenced them and then read that person. It’s a great concept. For instance, if you love Thomas Sowell, you’ll swim upstream to read Adam Smith. If you love fiction author Craig Johnson (creator of the Longmire Series) and swim upstream, you’ll hit Don Quixote and Dante’s Inferno (among many others, Johnson sprinkles in his favorite authors in almost every story). It’s a fantastic concept, and it’s an easy way to get “deeper” books.

Jacobs eschews most “lists.” I argue for a balance between Mortimer Adler and Alan Jacobs. The Great Books are cornerstone books that wielded, and continue to wield, massive societal influence. And many of The Great Books are enjoyable and insightful. Eschewing that list entirely, though Jacobs isn’t saying that, would be unfortunate. But most lists, as Jacobs rightfully shows, are constraining and often lame. But lists can offer a guideline to a topic or a theme or, especially to me, get you closer to a person you respect or admire.

My position, create your own lists. Find the writers or figures or even a friend you admire, and start with that. Swim upstream. You can do this on any topic. And make it your own. If one or two or more voices provide a wealthy resource of books, keep going with it. If you find a vein you like, go with it. Make it your own, and let your curiosities and enjoyment lead the way.

If you’re a serious reader, if you want more enjoyment from reading, if you want to read better books, if you wish to improve reading — read Jacobs. It’s a quick read, but it will unlock a whole other level for you. It did for me, I bet it will for you.

The Growth of the Soil, Knut Hamsun

Before I read The Growth of the Soil I ranked Don Quixote as the greatest piece of fiction ever written. Then I read The Growth of the Soil and it’s now, in my humble yet accurate and as true as gravity opinion, the greatest fiction of all time. In case you’re curious about my ranking…

(2) Don Quixote

and…

(3) The Idiot.

Some of you may have heard of this book, but many of you, likely have not. And not hearing of it is a distinct story.

Why?

Well, why wouldn’t you have heard of a book that won the Nobel Prize in literature?

And why wouldn’t you have heard of an author that rose to the heights of literary fame, a man once more revered than Hemingway, a man whose novels and prose changed writing?

Yes, Knut Hamsun at one time was one of the most revered authors and literary figures in the world. And he isn’t that old in the grand scheme of things, he wrote from 1877 – 1952.

So why haven’t you heard of this book, published in 1917, that garnered incredible acclaim?

Well, it doesn’t help when the author fawned over Adolf Hitler and Nazi ideologies, and it gets worse when you write a hagiographic eulogy of Hitler.

Hamsun is a peculiar figure, to say the least. Now, in most of Hamsun’s esteemed literature, we find zero Nazi ideology. Only a dishonest person would claim Hamsun’s agrarian sentiments make him a Nazi. The philosophical argument of whether we should or should not ignore Hamsun due to his love of Hitler has been going on since his passing. He was Norway’s literary hero, now, to Norway, it’s “how do we approach him?” I’m not going to get into the philosophical debates of whether he should be remembered. I’m not going to do the eye-rolling and pathetic, “trigger warning.” Hamsun was a man of his culture and time and believed in an abhorrent political ideology, and, despite today’s beliefs that only a handful of people liked Hitler (or the current accusation that Republicans are Nazis) or works like Hannah Arendt’s Banality of Evil claiming it was faulty thinking — during Hitler’s time, many around the world found Nazism a great belief. It wasn’t. It was awful. It was abhorrent. That’s not an apology for Hamsun. It’s my attempt at context. The Growth of the Soil is a masterpiece. It’s filled with rich insights into personal values and rich insights on how modernization can corrupt. It portrays personal relationships, human psychology, and a prose style that’s compelling, endearing, and poetic. It was once considered one of the greatest novels of all time, but Hamsun’s legacy has made it a philosophical debate. Where I stand, it’s a masterpiece work that’s worth reading.

Moving on.

The book got on my radar via Victor Davis Hanson. On his podcast, The Victor Davis Hanson Show he covered his favorite books, and this was his top (he detailed the Nazi bit, detailed the legacy and how to approach it, and did so better than I did). Like many, I had never heard of it. But Victor Davis Hanson is a favorite thinker of mine, and his knowledge of the world and arts is superb. When he said he loved it, I put it on the list to read immediately.

From what I gather, translation is critical. I talked to my best friend’s wife who is from Norway. She said Hamsun wrote in an old Norwegian style, yet what made him peculiar, he used old prose with Norwegian new realism. Norwegian new realism I will not dissect. But the Penguin Classic translation I read was fantastic. Continuing on the prose, what struck me, the poetic nature and cadence. It read a little similar to Dostoyevski’s tumbling out beauty, but Hamsun sucks you in. In other words, in some classic literature like Dostoyevski, while the sentences are beautiful and readable, you need to work through them a little. Hamsun, on the other hand, pulls you right in. His sentences are beautiful, compelling, concise, poetic, and make you want to read on.

Values. The story portrays personal values. The story details values interacting or clashing with other people’s values, and even the values of society or the environments and the various cultures surrounding people. Hamsun’s main character is Isak. Isak emerges from the woods to start a farm. While not an intellectual, he owns land smarts, and knows the value of hard work, and being true to himself. He’s unaware of his personal values, yet he has them, loads of them. And we get the story of his family, then his neighbors, then the various other characters, and then the ever-changing world and its various values. And Hamsun portrays the values in multiple ways, but he roots values, or the contrast of values, and compares them against two symbols: Sellanraa (the name of Isak’s farm) and the City.

It hit me recently. Many describe the story as biblical. I know a bit of the bible having read it once long ago. But I never gave the biblical element much thought, until I reread Genesis 1 and 3 recently. I was eating dinner, thinking of a recent Church sermon I attended, I turned around and looked at my bookshelf, and then it hit me. What hit unlocked more of the beauty and insight inside the Growth of the Soil. Let’s look at the lightning bolt that hit.

Genesis 1 is the creation story. Genesis 3 is when Eve gets tricked by the snake, bites the apple, and gives the apple to Adam. The snake deceived Eve to bite into the Apple and told her that biting into the apple means she will come to know as much as God. That story symbolizes vices or ideologies that can corrupt or mislead both humans and civilizations — the apple, biting into it, corrupts. Hamsun uses “the city” or “cities” to portray a certain set of values, and inside these values, exist ideas, philosophies, and ideologies that can corrupt. And the cities symbolize to extents industrialization or modernization. What hit me, “the city” is biting into the apple, it represents the allure of urbane beliefs and worldly pleasures, but it’s a ruse. It misleads — or creates — people into having a corrupted value system. Note, Hamsun doesn’t moralize. Hamsun shows living a superficial life and mistaking it for a deep life leads to emptiness. He shows temptations to find our utopia, skipping what worked in the past, leading us to unhappiness. And he shows that dishonesty, impulsiveness, and envy — all lead us to turmoil.

On the flip side of this, Hamsun used “Sellanraa” to represent ideal values. And the biggest thing that hit me, Isak is a character that never bites the apple. Isak isn’t perfect. He’s flawed. He’s aware of his flaws to some degree, as Hamsun adeptly shows. But Isak knows or senses the apple, he knows it corrupts, he’s aware of it, so he instead forges on, working hard, working to uphold himself to good values. And even as Isak attains incredible wealth and recognition, he never once bites the apple. It’s a gorgeous story Hamsun does well. He takes man, a flawed and tragic being, but makes that man not bite the Apple. And he does this in a realistic manner, without making Isak boring, moralizing, or goody-two-shoe’ed perfect.

This delivers the reader a beautiful and insightful story. “City values” interact with “Sellanraa” values. We see characters move near Sellanraa, thinking being a farmer is easy and expecting to live country gentleman lives, but the idealized vision fails. They lack a work ethic, get jealous of Isak’s success since they see Isak as a rube, and they despise the Sellanraa values. Yet Hamsun throws in nuance, it isn’t a binary, black-and-white story of opposing values battling it out. We get rich insight into love, fatherhood, honesty, dishonesty, modernization, and more.

What I found deeply interesting and moving — the depiction of relationships. And how “city” values interact with “Sellanraa” values. For example, without trying to give away too much, Isak’s wife goes to prison for a few years for infanticide. She came from Sellanraa, went to prison, but at the prison, became “cultured” — aka she bit the apple. Granted, Hamsun shows a few of the benefits of her gaining culture, but she gets lured into taking more bites of the apple, and it corrupts her. And when she returns to Sellenraa we see the clash of Isak’s ideals with his wife’s newfound city values. I won’t give away anything, but her corrupted values cause pain for Isak, and, pain for the reader. Likewise, we see one of Isak’s sons go off to the city, and we see a boy trying to escape his roots, trying to shed everything he sees wrong with his family, and trying to shed what he sees as unhip traditions. While Isak’s other son and daughter, find a home with “Sellanraa” values. This play on values makes not only compelling reading but touching, moving reading. And with the relationships, I wanted to grab Isak and put a better woman in front of him, the same with his neighbor. I wanted to play matchmaker. And it was visceral. Now, had Hamsun chosen to give Isak a wife complementing his values wholly, it would have made for boring reading. We wouldn’t see the rich lessons and insight. We wouldn’t be able to walk away with what The Growth of the Soil offers us. Not that a wife complementing him would be implausible, as in, if Isak knew a bit of vetting, he could have easily found a woman that complemented him. And Hamsun teases us with this possibility, but, again, if Hamsun wrote that, it wouldn’t offer him the creative canvas to paint that insight. We’d miss the cautionary aspect of not vetting for a good partner.

A masterpiece work.

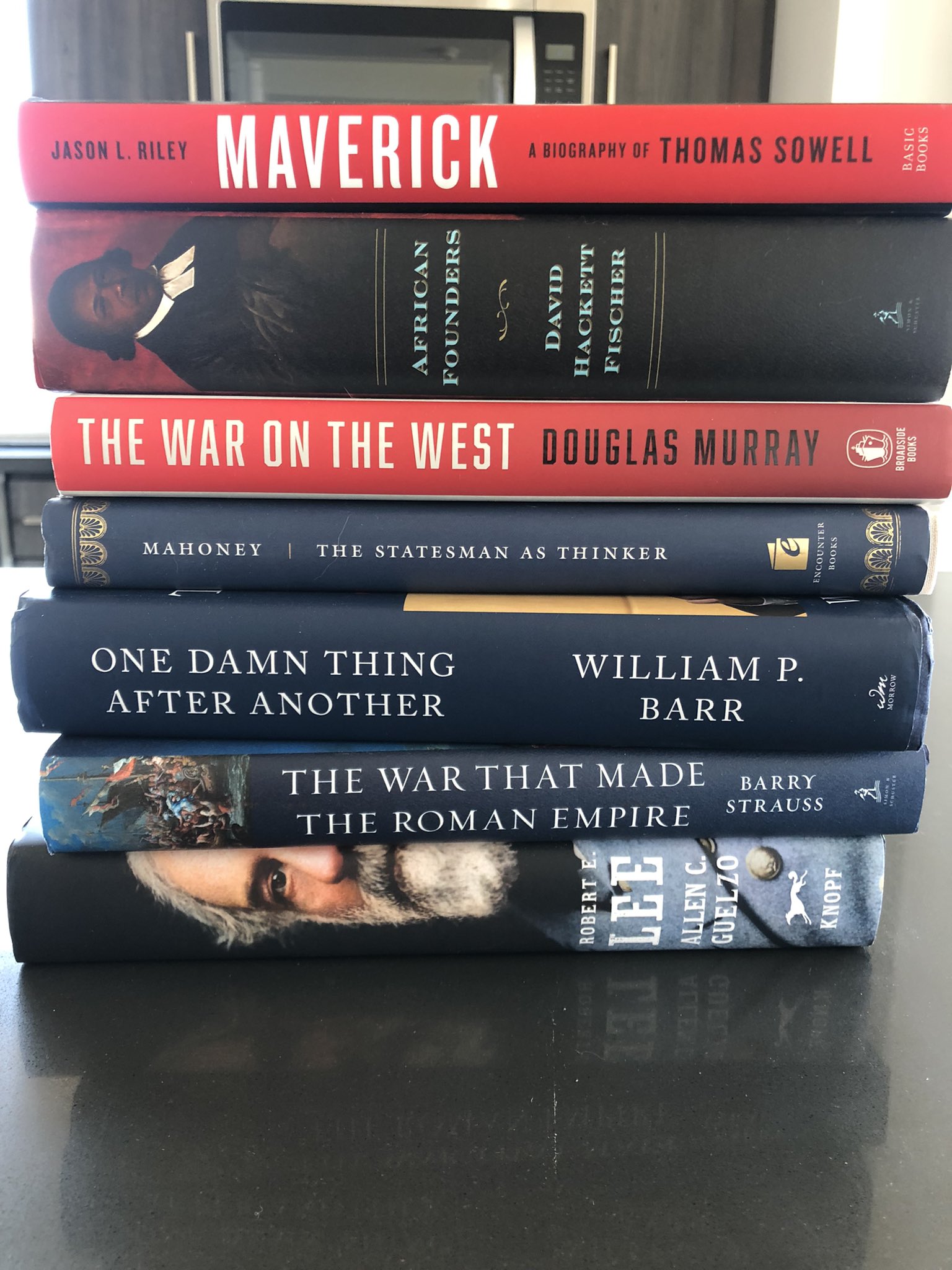

Statesman as Thinker, Daniel J. Mahoney

Nietzsche and Machiavelli fans will hate it. Christians will love it.

Mahoney delves into Statesmanship on the surface, but he’s really making a case for what’s missing in today’s political leadership, what’s hollowing society out, and what ideologies are leading to decay. He offers a few key figures who were ideal statesmen. The key figures standing out to me: Edmund Burke, Alexis de Tocqueville, Winston Churchill, and Abraham Lincoln.

The book is advanced. Mahoney writes to a well-read audience.

One, a dictionary is needed. Not that he’s purposely using big words, he’s using the right words, yet some of them need clarification to the philosophy he’s detailing. Two, a philosophical dictionary of sorts is needed. Mahoney is concise, but he will say “Nietzschean” in a way that if you’re not familiar with Nietzsche, in particular Nietzsche’s Ubermensch concept, you will need to look it up. In summary, and injecting personal opinion, Nietzsche reads wild, offers some cool philosophy, but he’s nihilistic regarding traditions, and, in a way, pushes a grand narcissism. If you’re wondering why people are saying “cancel the classics!” at school, that has a Nietzschean flavor; in short, the idea of putting self over inherited traditions, and putting self over anything — God, community, family, traditions, and so on. Nietzsche’s philosophy serves as a great impetus to motivate oneself; Nietzsche’s philosophy serves as a great impetus to undertake a nihilistic and narcissistic worldview. Mahoney lays this out in clear, concise detail.

I found certain portraits of the figures Mahoney details powerful and insightful, others less so, and those others seemed more or less a recap of what some other thinkers thought of a person. And sometimes, the portrait served as a clarification or an argument against detractors. At times things got a little repetitive. Regardless, it’s a solid read, it’s insightful, and it’s a wonderful introduction to certain figures like Edmund Burke or Alexis de Tocqueville.

I mention Christians will love it. Why? Mahoney bakes the importance of Christian ethics into his writing. For you non-believers or agnostics out there, you can still enjoy the book. Despite the mistaken beliefs, Christian ethics isn’t televangelical beating over the head of the Ten Commandments and that an angry, spiteful God is watching your every movement. Christian ethics are much like Aristotle’s ethics, but a little less egalitarian than Aristotle’s (that’s the standard consensus, I disagree a bit, but that’s not the topic of this piece).

To finish, while the book sits in the political philosophy realm, insight exists regarding Success. In particular, the virtue of integrity, versus the nihilistic belief of making self-worth depend on conversions, attention, reading hustle porn, and making money.

Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell, Jason L. Riley

Thomas Sowell is my intellectual hero. I’d say he’s also a hero of mine, period. If you’re a longtime reader of mine, you know all this, and perhaps are bored of hearing it, but, too bad, you will keep hearing it.

Jason Riley is a Conservative thinker and writer. I’m familiar with his writings from the Wall Street Journal. I was excited to read this biography. One, it’s written by a writer I like, and two, it concerns my hero. A good combination. The book did not disappoint.

The biography more or less details Sowell’s work, his philosophies, his critical work, and how it all shaped and evolved. And details why Sowell’s being black and Conservative keeps Sowell from getting Nobel Prizes, despite his work being empirically far superior to many winners. The biography does detail parts of Sowell’s life, but Riley focuses on what comprises Sowell’s philosophy.

Sowell grew up in the Jim Crow South, in abject poverty, before moving to the slums of Harlem in New York City. He displayed a prodigy-like mind at an early age. Politically Sowell started out as a radical black Marxist. In fact, his earliest college papers were on Marx. Yet he shifted his political beliefs to become, arguably, one of the greatest Conservative figures of all time. And, no matter your political beliefs, Sowell is a thinker that will leave an enduring legacy.

The lessons in this book are plentiful.

For you Sowell fans, you get a vast look at Sowell’s work. And it’s eye-opening. His economic work, sadly, has been kept relatively hidden. Yes, kept hidden. He’s a black conservative empirically disproving many popular theories. And he gets castigated for it, horrifically so, by left-leaning political thinkers. They say he’s “an Uncle Tom” or he’s “been whitewashed” or he’s “serving his master like a good n———”

Which is utterly appalling and unfortunate. Sowell’s work is groundbreaking, he covers a wide territory, and he’s readable.

For those unfamiliar with Sowell, but curious, you’ll find a great introduction. You’ll discover the vast topics Sowell has covered, and some books and works to start with. You’ll also learn the gravity and impact of Thomas Sowell.

Biographies, real ones — not the hagiographies Ryan Holiday’s company, Lioncrest farts out — offer manifold lessons. Lessons we can walk away with and apply in our own lives. One such lesson from Sowell: stubborn and hard-headed self-determination. He valued good teachers, he valued rich insight from past thinkers, but he was determined to do it his way. In the realm of Success, we need more of that hard-headed self-determination rather than the find a guru to tell us what to do and give us permission to do it. Sowell questioned everything. When his famous professors Milton Friedman and George Stigler told him to do things or avoid things, or check out a guide to help him with a book, he said, “I’ll figure it out myself.”

I love that.

Instead of reading every single Gary Halbert letter, going through every single Tony Robbins book, figure it out on your own. And work hard at it. This isn’t a call to not asking questions, this is a call to get self-determined; to ground your principles, convictions, and instincts — without the need of gurus translating how your path should go for you. That stubbornness is a good quality. That hard-headed determination is a tonic most would do well to drink from.

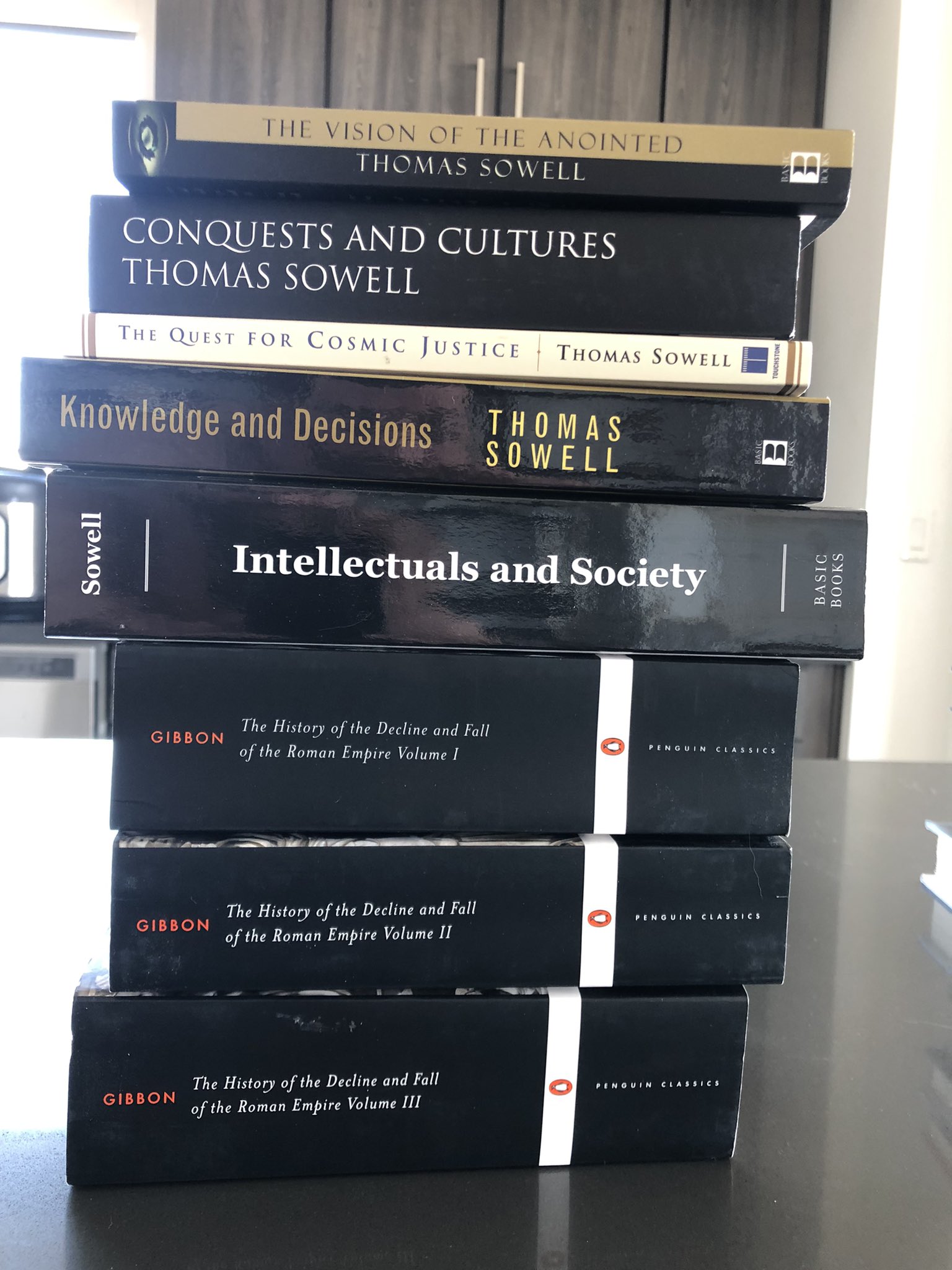

The Vision of The Anointed, Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell said he’s most proud of Conflict of Visions. In my opinion, if you read Conflict of Visions, you will never see the world the same. Conflict of Visions is one part, or the main part rather, of a loose trilogy: Conflict of Visions, Quest for Comic Justice, and The Vision of The Anointed. In a sense, Conflict of Visions lays out the argument and its terms, while the other two works unfold the philosophy and arguments.

The Vision of The Anointed details what Sowell labeled in Conflict of Visions as The Unconstrained Vision. Here’s a quick definition of both visions. The Constrained Vision believes that man is flawed. And that the collective knows more than one expert on the whole. That means traditions, localism, community, and what we’ve inherited from society and our forefathers give us much wisdom and stability. This vision wants the rules, the laws, to be simple, as in, like the rules of Soccer. Everyone plays by the same rules; disparities will happen, but that’s part of nature. Whereas the Unconstrained Vision believes not in processes but solutions. They feel that man and society can be perfected, and usually, the experts or those with superior knowledge will lead us to the promised land. They reject the rules for the Soccer game, they want equality in the outcome, they want the disparities eradicated, and wish to create rules to do so.

This work details the Unconstrained Vision. For you political nerds, this looks largely at more left-leaning politics and the consequences of the solutions proffered. Sowell unpacks legal, economics, race, income, and more. He also details the history of this vision, the thinkers and ideologies leading to it.

It’s a fascinating work. You can read this book if you haven’t read Conflict of Visions. In fact, it’s more approachable than Conflict of Visions.

Political theory or philosophy aside, Sowell is a master of psychology, human nature, and critical thinking. Read enough of him, and you start asking questions. You see through the rhetoric, the hyperbole, and the hot air of nearly anything — and not just politics or race. Sowell owns a remarkable talent for teaching you how to ground something in reality. He loves the simple “then what?” line of thinking. Since a few “then what’s? on a big claim often leads you to, “well, I dunno.” But Sowell shows you how to find the tradeoffs, and if the tradeoffs aren’t there, to then spot the bullshit.

It’s fantastic, anything Sowell is fantastic.

The War on The West, Douglas Murray

Douglas Murray is a bit of a firebrand Conservative author, his book The Madness of Crowds gained notoriety and success; The War on The West was my first go with Murray, and a few people said it was going to rock me — I found it underwhelming.

I found he didn’t address anything new, and not that he needed to, but the argument felt underwhelming. I felt his examples boxed him into a narrow space, and while he used good examples, it’s like he left them hanging on the surface. It lacked the rhetorical vigor and depth I expected from a firebrand personality.

But I wouldn’t take my review as a reason to not read it. On one end, if you’re curious to learn some of the “Woke agenda” and why it’s decried, War on The West offers a decent introduction. You’ll find out why Conservatives in America and Europe (though European Conservatives are different, but that’s philosophical quibbling) decry things like Critical Race Theory, Social Emotional Learning, Pronouns, Gender Transitions, and so on. Murray focuses primarily on race and the double standards of those castigating the foundations of Western civilization. It’s a fast read, clear, and concise.

But to harp on language, yes it’s clear and concise, but it lacks punch, substance, and depth. Murray writes a safe book. He tosses red meat to his audience, and that’s the extent of the book.

In my opinion, if you really want a book with weight and punch, with substance and depth, and a book arguing beyond a shadowboxing jab, then go with either The Dying Citizen by Victor Davis Hanson or White Guilt by Shelby Steele. Both are far superior. Each offers substance and background; each marshal a strong argument; and, finally, each goes beyond tossing red meat to their audience.

Classical English Style, Ward Farnsworth

“Use small, simple words!”

“Write short sentences!”

“Big words are used by those who want to sound smart. Don’t do it! Use small words. Write in the active voice only! And avoid adverbs!” (I hope you see the contradictions.)

That advice pervades modern writing. And modern writing and reading today, much of it adhere to that advice. Popular fiction and non-fiction feature short sentences, small one-syllable or two-syllable words. And it’s getting boring. It’s starting to sound the same and look the same. It’s an outright myth and false claim that big words and long sentences are used only by those trying to sound smart or academic. Yes, academic writing is comedically bad, but also comedically bad is its opposite — the generic modern writing style pervading books, blogs, and social media today.

This book is an antidote to the generic, wooden, watered-down prose infecting modern writing. If you’re a serious writer — read this book, immediately, yesterday if possible.

Farnsworth begins this work with a way to simplify how to understand words and prose. He divides it roughly yet aptly between Saxon words and Latinate words. For instance:

- Saxon: see

- Latinate: perceive

Latinate words can change and alter into an -ion word or other forms, like perception or perceptive. Saxon words are more informal or easier, like ‘see’. Now, some Saxon words are big, and some Latinate words are small. But Farnsworth shows how Saxon and Latinate provide a good compass: Saxon = simple and small; Latinate = fancy or formal. From here, Farnsworth builds off how great writers of the past and current use a mix of Saxon and Latinate words to powerful effect. And as he teaches he busts many style myths.

For instance, “using big words to sound smart” equals, as the theory goes, “using big words means you’re an insecure douchebag that knows nothing about writing to make money online.” Ok, I took some liberty in my example. But that big words to sound smart is largely a myth. Where it is correct — academic journals and jargon. Current academics can’t write their way out of a brown paper bag. They dump nouns on the page. It’s a prolix mess. And yes, Academics tend to live in their tiny bubble, adoring their pet theories, and ejaculating meaningless jargon onto the page that other academics seemingly like. Let’s walk away from the Ivory Halls of self-indulgent Intelligentsia and into reality. A common and good piece of writing advice is “use the right word.” Well, sometimes the right word or collection of words is the big word or the Latinate word. For a simple reason, one can use a Latinate word for a stylish effect. A writer can start their sentence with many small Saxon words, one or two-syllable words, and then end that sentence with a big Latinate word for effect. “On Twitter, we see gurus giving writing tips, they say ‘use small words’ and ‘write short sentences’ all fine and well, but many of these gurus are sciolists.” That Latinate ending is a style choice. A writer can use that fancy Latinate word for rhetorical effect or use that word to introduce ideas or an argument. It all depends on the context.

In my example, depending on my aims, I can use the fancy sciolist word at the end for rhetorical effect. I can use the Latinate ending here to encapsulate gurus and simultaneously lay bare the weaknesses of gurus and their ideologies. In other words, I can drag gurus into a boxing ring, tie their hands behind their backs, and go to town on them. I can also use the Latinate word here in my example as a transition device. I use guru prose as an example, then use my Latinate word to introduce or transition to an argument. As in, I take the small, on-the-ground ideas, use a word to create a more formal arena of ideas, and then go from there. Many more uses of Latinate words exist, it’s not limited.

On the flip side, a writer can use all Latinate words and then end the sentence with a Saxon word. Like above, it can be used for rhetorical effect. Or, also like above, you can use it to transition into an argument or premise. For instance, you can take the high and mighty language of Intelligentsia, the big noun words, and make them look like out of touch idiots. “The application of Michel Foucalt, the moral relativistic inclinations he propounds of systemic oppressions, and his disputations with traditions disclose a singular factual reality of Foucalt, he’s nuts.”

Farnsworth, however, goes deep. He shows the effect of Latinate sentences unpacked with Saxon sentences. As in, an author lays out big ideas and arguments with Latinate words, and in the next sentence, the writer uses Saxon words, saying the same thing as the Latinate words, but the Saxon words, as is their purpose, grounds the lofty ideas to concrete reality. On the flip side, the writer can start off on the concrete, writing Saxon words, and then in the next sentence, say the same thing, but using Latinate words to show that the ideas go beyond the concrete and have some lofty weight to them. And Farnsworth teaches a variety of style tricks and methods.

One thing making Farnsworth special, once he shows it to you, you can’t unsee it. And he gives you a way to practice it and apply it instantly. You may not remember the name of the method or the rhetorical trick and say “ah, that’s a metonymy” but you will recognize the skeleton.

What I did not expect, the Classical English Style will unlock works for you. I wish I had read this before I read Edmund Burke, David Hume, and The Federalist Papers. Classical English Style is a Rosetta Stone of great works. Farnsworth laments over the loss of style. He says how prose masters like Edmund Burke and Abraham Lincoln were accessible and powerful writers. But the myth of “short writing” made the greats like Lincoln seem too heady. He argues that Saxon only writing restricts writers at times, and it can weaken an argument (my point on Murray is a perfect example). And he shows why this modern day prose gets boring and unsatisfying and, I’d say, eye-rolling. Yet once he shows you a little of the Classical English method, suddenly certain books that seemed “well this is old arcane writing” popped to life. The writing gets clear, magical, and compelling. I read this work right before Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments and it unlocked that work for me. While it took me over a month to read Theory of Moral Sentiments, Farnsworth made it accessible, made it come to life. I could see the arguments, the effects, and just how great Smith is as a writer. So if you’re looking to read some classical works, and want them to be readable, read Classical English Style.

And to leave off, for you writers in my audience, Farnsworth will challenge and inspire you to write better. He also curates some of the best and most memorable sentences ever written. You’ll want to read them aloud, chew them over, and unpack them. It’s a must-read for serious writers.

Billy Budd, Bartlelby, and Other Stories, Herman Melville

Hilarious. Melville is most famous for Moby Dick. I never read any Melville before. I expected a stern style. But I laughed my ass off.

I read Bartlelby, the Scrivener. It details the story of an office that does a bit of legal work but works at doing the bare minimum. And a man named Bartlelby shows up, does sterling work his first day or so, then rejects more and more work, saying, “I would prefer not to.”

Melville deploys the Classical English Style mentioned above to hilarious use. For instance, the main character of the story is the owner of the office. The owner has a self-righteous, overinflated sense of self-importance, and he’s aware of his insecurities. Melville takes this self-importance and uses long, ambling sentences with Victorian words to then end each sentence with a wry, near slapstick ending. As in, he describes the beauty of the office, and the joy of having a window, and that window has a view, it views the black, smog stained brick wall of the building next door, a building a few feet away.

The story offers a tragic madness and a tragic comedy of Bartelby. We have no idea where he came from, what his background is, or why he prefers not to. He causes near madness to anyone encountering him, yet we feel for Bartelby.

It’s a fantastic story; it’s hilarious.

Not Read

The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge, Calvin Coolidge (Introduction by Amity Shlaes)

When I was a young boy, my dad took me to the hometown and homestead of the Coolidge clan, Plymouth Notch, Vermont. By total chance, I shook the hand of Calvin Coolidge’s son, John Coolidge. At my age, and being a history dork kid, this to me was like shaking the hand of the son of a superhero (did I mention I was a dorky history kid?). I didn’t really know who Coolidge was when I was a boy, but I was able to grasp that shaking the hand of a president’s son was special.

Coolidge is a president often overlooked and misunderstood. Franklin Delano Roosevelt deserves the blame for how Coolidge is received today. Why? Under Coolidge’s presidency, America became exceptional. When Coolidge took office, flight was barely a thing, when he left, commercial flights were a thing. No, he didn’t singlehandedly do that, yet his policies raised the standard of living in America to incredible heights. He had the lowest unemployment in history. He had the best economy in history (even riding out two recessions that started worse than the Great Depression), and the deficits and budgets and debt, the US has never gotten back to, or close to his level. Minorities also made incredible advancements during his tenure. In sum, life was pretty good with Cal at the helm. When the depression hit, FDR noticed that people yearned for the Coolidge days. So FDR ran a marketing campaign blaming Coolidge for the current depression, and that only he, FDR, could save the country. As a result, FDR swept Coolidge and his accomplishments under the rug. And fun fact, the standard of living America enjoyed during the Coolidge years didn’t return until the mid-1950s, an astonishing thirty years after his presidency.

In my humble, but packed full of accuracy, insight, and truth opinion, Calvin Coolidge is the second greatest American president, maybe the greatest. I rank Lincoln the highest, and Washington third.

Calvin Coolidge loved to write, and he wrote in a terse, wry style. Amity Shlaes wrote the introduction to this autobiography, and her biography of Coolidge is superb. The history dork in me is alive and well, so I’m looking forward to reading it.

Breaking Bread with the Dead, Alan Jacobs

Two reasons have me excited to read this book, and one reason is, I admit, perhaps a little petty or judgey (yes, I’m judgmental, or “judgey” as someone once said). My petty reason, Alan Jacobs destroys Stoic popularizer, Massimo Pigliucci in this book. Massimo Pigliucci does offer an ok gateway into Stoicism, but he morphs Stoicism into a secular, morally undemanding ethical system, and also into an Epicurean buffet like philosophy, as well as pushing hardline progressive values. In short, Pigliucci is a moral relativist, a Stoic relativist, and he’s a smug asshole. Jacobs calls out why Pigliucci is wrong in this book. The immature side of me, the side that lowered the bar of decorum and called him a smug asshole, enjoys that.

But the main reason, Jacobs goes into reading the classics. As you can tell, I loved Jacobs’s other book, so I’m looking forward to this one.

The Content of Our Character, Shelby Steele

Shelby Steele is a dangerous man. His book White Guilt displayed the prose of a masterful sword fighter. He wields arguments and truth with a deft, masterful touch. He’s a favorite thinker of mine, his documentary, What Killed Michael Brown is utterly fantastic (watch it), and this is the book that made him famous.

The Square and The Tower, Niall Ferguson

Another favorite writer of mine. Ferguson is a superb historian and prose master.

Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift

I’m working on reading some more classics. Gulliver’s Travels is a Great Book and a famous satire. I can’t recall if I read any of it in high school or college, but I’m looking forward to digging into it.

The Iliad, Homer

It’s the oldest story we have. It’s the first book in The Great Books. I remember some pieces of it from high school, I know it’s a bit of a slog compared to The Odyssey but it’s a foundational work.

African Founders, David Hackett Fischer

I’m reading two time period rabbit holes. One is around the Founding Fathers or the birth of America. The other is the 1920s and into the 1960s. I got three more Founding Father period books to go, this being one.

Fischer is a renowned historian. I heard and read reviews from sources I trust. And on the Bookmonger Podcast(a good source for new books) I enjoyed the author’s easygoing manner and his insight. The book details the culture enslaved people brought with them and why that culture endures.

One Damn Thing After Another, William P. Barr

William Barr is an interesting man. He served as attorney general under two presidents, George Bush and Donald Trump. Two sources I respect recommended this book, Andy McCarthy (a famous attorney) and author Jack Carr.

The War That Made The Roman Empire, Barry Strauss

I heard Strauss on a few podcasts, and I heard Victor Davis Hanson mention him. The premise of war he details sounds intriguing.

Robert E. Lee, Allen C. Guelzo

After I finish my Founding Fathers’ era rabbit hole, I’m eyeing the Civil War era. Robert E. Lee has been canceled in America. Presentists’ (people who adhere uncritically to present day attitudes, and force history into the lens of fashionable moral standards) cast Lee into their “all things bad” pot. I’m not hailing or revering the Confederate South, but ignoring its history and ignoring its figures or reading them through the tribalist lenses of Nikole Hannah-Jones (The 1619 Project) is a failure.

Guelzo is also a superb historian.

Conquest and Cultures, Quest for Cosmic Justice, Knowledge and Decisions, Intellectuals and Society, Thomas Sowell

With my love of Sowell, I think you get what I would say here.

From what I hear, Knowledge and Decisions is an economic masterpiece. And Intellectuals and Society is a prescient book, a book hated by people like Robert Reich or Paul Krugman.

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon

I’m eyeing it. I’m feeling it. I’m desiring it.

No, I’m not getting naughty here. I have an intimate relationship with reading. And I’m sharing something perhaps odd.

I eye books.

I sometimes have a long flirtation with them before I read them. Sometimes, I want to read them sooner but I focus my energies on a different book. But then I return to that book. I didn’t pass on the book because I felt it was unworthy or liked it less. It’s that the timing wasn’t right. And then the time is right. And I feel that the right time approaches to read The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is a behemoth. Each volume in the picture contains well over one thousand pages. It’s a famous volume, a volume still wielding enormous significance in the world. I’m planning to read it soon, perhaps in the next few months. It’s calling me. Yes, to get even weirder, I get a feeling a book calls me to read it. I plan to read some books first in preparation to tackle this behemoth. And I know reading this behemoth work will take me the better part of a few months.

I believe this will be my winter season read.

- This “read a book and see” exemplifies issues with modern reading. The issues tie to the long decline in many Western education systems, and, I argue, on how Gurus tell us how to read. The main issue, a lack of critical engagement or questioning of a book. We are taught that books offer lessons. And with all the tips and tricks, we look solely for lessons versus critical engagement with a book. So we sit back, ask no questions, and seek lessons. When good reading, as does good thinking, requires you to engage critically with a book. This person telling you to read “this book” as a way to change your opinions, likely never questioned that book. ↩

- Thought-terminating cliche is a bit of a fallacy. A person ends the debate or conversation with a cliche instead of a point. And that cliche is designed to end the conversation. Here it’s “you should really read book X.” (We could quibble and say this is an appeal to authority as well). Another example would be, “stop thinking so much.” This misdirects the attention as if the person is overthinking.