They battle inside our email inboxes.

Your inbox. My inbox. Your neighbor’s inbox.

Businesses battle for our attention.

Travel sites, bloggers, clothing companies, and that weird knickknack place where you bought that cat coffee mug—each battle for your attention.

Three spirited men recently battled for my attention: Jason Capital, Garrett White, and Mike Cernovich. Out of those three, two still battle for my attention, one doing so almost hourly. And these two spirited men use standard, popular, and dependable marketing tactics. In fact, they even teach these tactics to entrepreneurs and businesses.

The first two hammered my inbox using faithful email marketing tactics like curiosity-triggering headlines, body copy that deployed promises, open-loops, and scarcity. Through all of this, they tried to coerce me to click a link. When I clicked, they shoved me to sales pages that hit me with more faithful and popular sales tactics, like reason-why copy, raising curiosity, problem selling, social proof, claims, big promises, and blatant selling.

But the other guy took a different approach. He showed up like Clint Eastwood in a Western: self-assured and credible. He sent a simple yet potent email. One email. His sales page stands as one of the best I’ve seen, read, and studied. Those three guys who are battling for my attention exemplify the good, the bad, and the ugly of how marketing tactics can either help or hurt a business.

We exist in a direct marketing world. Daily, we’re on the receiving end of direct marketing tactics and strategy. Social media, Amazon, company landing pages, blogs, podcasts: direct marketing occurs nearly everywhere in our lives. Direct marketing, in short, is marketing aimed at an individual. This marketing style tries to foster a one-to-one selling environment. Our email inbox exhibits a prime example of direct marketing.

Today, any business—or person—can pick, stack, and deploy countless direct marketing tactics to grow a business or sell more products. Tactics—like funnels, copywriting, conversion algorithms, landing pages, segmenting, influencer marketing, content marketing, targeted ads, media buying, video sales letters, newsletters, sales letters, texts, and too-many-to-list methods—can raise a business’s chances of succeeding.

Similarly, entire industries now exist on the backs of those tactics. You can buy an online course on copywriting, or a major corporation can hire an MIT calculus whiz kid to head their media buying analytics team. And that vast tactic arsenal is now available to anyone—or any business—at practically any price range. What costs a fortune to a blogger and what costs a fortune to Proctor and Gamble can be spent on utilizing, testing, and deploying direct marketing tactics. Although direct marketing tactics wield immense selling power, they can also destroy your business.

Marketing, of course, matters. Any company or business, from a single blogger to a Fortune 500 company, requires sound marketing. Shrewd marketing helps build and sustain a business. Today, we can track the results of many marketing methods, and this helps businesses see both opportunities and advantages.

Businesses can no longer say, “Well, we ran an ad, and it seems like more people came in!” Detailed testing, analytics, and metrics now determine how strong or weak an ad performed. We see the results instantly. For example, in the 1980s, it took weeks to see how a split-tested ad in a newspaper performed. Today, depending on the traffic source and size, you can run 24 split tests, creating a virtual split-testing playoff bracket, starting at 7:00 a.m. By 9:00 a.m., you’ll have a clear frontrunner to send to your entire email list.

On the other end, if you’re not split testing 24 headlines and you created your first website, you can quickly split test your landing page copy. As you develop your business, you can quickly and cheaply develop your copy skill and learn what ad copy, what terms and phrases, best suit your business—a vital tool now available to anyone who’s never written copy.

Undoubtedly, marketing tactics and metrics play a vital role for any business. The tactics can offer alluring profits, and the metrics provide addictive measurements. But underneath the surface lies a landmine—we often lose sight of the fact that the product must carry some serious weight. Likewise, the business model—the profit model, the revenue model, the accounting, and the business’s purpose—can’t be overwhelmed by blind growth. Falling in love with tactics, rapid profits, and growth at all costs often manifests weak products. In fact, in many cases, heavy-handed marketing hides flimsy products and often shows a scrambling business.

Now, the three take-charge men who battled for my attention each appeal and generally market to men who want to be better men. They want to be better at business, better at making money, better at relationships, have better sex lives, and use better self-discipline. Two claim to be polarizing; one is polarizing without requiring boast.

I’ll note, ideologically and philosophically, I don’t subscribe to much of what these guys represent, but I think it’s fun to toss into the ring three men who publicly represent Alpha Masculinity, teach men how to reclaim or stoke their masculinity, and offer business lessons. But for the sake of this article, we’ll focus on their marketing. We’ll quickly see what separates the man from the boys. We’ll see who commands marketing skill and business acuity and who doesn’t.

Again, the three are Garrett White, Jason Capital, and Mike Cernovich.

Each recently emailed me to offer their exclusive events.

- Mike Cernovich: The Trip of Lifetime

- Jason Capital: The High-Status Summit Event

- Garrett White: Be The Man Challenge

The Generic “Guarded Secrets” to Grow A Business.

Garrett sent me—unless I missed a few or some went into my spam folder—15 emails inside of a week. I opened the emails (I open all of my marketing emails), but I didn’t click a link until I began research for this piece. I say that because, had I clicked the link, he likely would have segmented me into a specific group. That group would receive a different email sequence targeted to “users who click but don’t buy.”

Here’s what I mean: when you click a link in an email, you take what some email systems call “an action,” and your action “triggers an event.” The event: people who open the email and click the link but don’t buy the product get moved into a designated—“segmented”—email list. Then the marketer sends certain emails—all previously written and many previously used because they performed well—tailored to that specific segment. Next, either the marketer’s email list manager or the marketer’s email software then send the pre-selected set emails. Often, the batch sent to “opened, clicked, but didn’t buy,” utilizes email body copy that employs scarcity tactics like “seats are filling up fast” or “early bird discounts”—trying to coerce you to buy.

Whereas people who open the email but don’t click the link trigger a different event. The marketer will send a different batch of emails to those people and try psychological tactics to persuade them to click the link. For example, the marketer may say that someone already benefited from a cool trick they learned after clicking the link. Now, if you don’t open the email, the marketer still segments you onto a list. As in, your inaction still triggers an action. Here, you’re going to start seeing email headlines like:

- Goodbye,

- Bye;-(

- Your log-in access is being REMOVED

- DO NOT SHARE: Please Claim Your $1,500 Credit Today

- Confirmation Book Order #KTJ222174

- Where should I send your Free Book?

- Do I have your address correct?

- Re:re:re:re:re: your credit card was charged—should I send you a full refund?

- FINAL NOTICE: Fitness tracker on hold (need correct address)

These are heavy-handed headline tactics that the marketer uses to hopefully raise your curiosity or elicit your concern to force you to open the email.

Jason battered, and still batters, my inbox (as of this writing). He’s selling tickets to his High-Status Summit Event. I lost count of how many emails he’s sent, but it’s way more than 15. He also blasts me with countless emails for his other courses. These are mature offerings like, The Donald Trump ‘Dark Arts’ Persuasion Secret Which Helped Him Get Rich, Get Women, And Get Into The White House… And How You Too Can Use This Exact Same ‘Mind Sorcery’ To Become A Walking ‘Weapon of Persuasion.’1 I’m curious if the teaching requires you to be a scion to one of the wealthiest men in New York City, get gifted around $413 million in loans from Poppa Trump, then dig in hard on a win/lose negotiation style.2 Jason offers long-term career plans: a course promising how you can quit your job and get rich on Instagram. He promises to teach you the same bulletproof career plan that other everyday Jake and Jill’s—like the Kardashians, Dan Bilzerian, and Cardi B.—followed to quit their jobs and find fame and riches.3

Both Jason and Garrett use similar and popular direct marketing tactics. Their emails follow a similar headline and body copy template. Both follow generic email marketing formulas: early bird awareness, testimonials, and price scarcity (reality: the price stays the same). They use phrases like “Others are taking action; why aren’t you?” or “Last chance!” They then repeat the cycle.

Their email body copy—even the character width—uses a generic, and widely available, formula. Similarly, the email headlines are nearly word-for-word matches. Not only do their emails follow the same generic formula, but so do their sales pages, video pitches, and the scripts they use. There’s barely any difference.

Why the similarity? Don’t they claim to show you secrets, tactics, and techniques that barely anyone knows?

The reason is simple. There’s a wizard behind the curtains.

They both use similar tactics because both use a funnel they learned and purchased from Russell Brunson.

Russell Brunson is a savvy marketer who teaches and offers a paint-by-number marketing platform called ClickFunnels, which offers a marketing tactic arsenal along with Russell’s teachings. The marketing tactics are not only reliable but also shopworn. Basically, ClickFunnels works a little bit like WordPress, but instead of creating a blog or a standard landing page, ClickFunnels offers preset marketing funnels. Each funnel comes packed with common and popular marketing methods and tactics. The standard platform costs $297 per month (as of this writing). With ClickFunnels, you don’t have to hire coders or spend time trying to create your own funnel on a WordPress-style platform—it’s all set and done.

ClickFunnels also offers various upgrades where you not only access more Russell teachings, but you also buy more marketing tactics that you can plug right into your existing ClickFunnels funnel.

Russell and his team constantly study various sales funnels—including the ones they design for other people—that perform well in other markets. They then swipe, copy, and create numerous paint-by-number sales funnels that a ClickFunnels customer can pick and use for their business. This process can be done in mere minutes.

Jason and Garrett both use a ClickFunnels template. They use the Expert Funnel template, among others. What you see on their pages—the copy, the pitch, the layout—all follows Russell’s directions, almost to the letter. Albeit, Jason leans a little more toward Agora Publishing’s generic copy formula, but both still diligently use what Russell directs.

Nearly everything Jason and Garrett use follows Russell’s directions, which is a smart move for them. Why? Russell possesses uncanny business and marketing expertise. Russell studies marketing tactics, and he’s built an extensive marketing playbook that someone can buy and use. Nearly every tactic that Jason and Garrett utilize to run their business—the sales videos, the scripts, the page, what’s shown on the videos, the buy buttons—is copied from Russell’s playbook. Even the content—the lessons they teach—is mainly copied from Russell’s playbook. Jason and Garrett fit the stereotypical customers that Russell attracts.

Russell knows that a market exists for people who want fast riches. And he targets people whose businesses serve as a vanity project or who love seeing conversion metrics—like Jason Capital and Garrett White. These businesses allow people to call themselves experts and boast about success like Grant Cardone. Russell’s ClickFunnels platform offers a tactic arsenal—an arsenal promising shortcuts to making massive moola online. The tactics can work and work well, and not just for Grant Cardone or Tony Robbins wannabes, but also for businesses who want to market their product or service better.

Indeed, Russell offers a groundbreaking service. In mere minutes, someone can set up an online business or circumvent hiring a creative agency and set up a converting funnel. But here’s the issue: Russell offers and capitalizes on downstream marketing tactics. Ever hear the old saying, “the easiest sale is selling to a salesperson?” I find some merit in that saying. A marketing department, or a marketing-minded person, loves seeing their marketing perform well. Many are fascinated by selling psychology and reasons why people buy.

Russell promises and sells marketing tactics that promise a business fast growth and fast profits. But fast growth and fast profits blind many businesses in two ways. On one end, fast growth and fast-profit-marketing schemes allure vanity-project or guru-complex-afflicted entrepreneurs: people fascinated with money, obsessed with status, and often believing that external markers of success equal self-worth. These businesses tend to be shortsighted and short tail. As in, the guru must constantly scramble to stay relevant.

On the other end, which I find more insidious, ClickFunnels represents common beliefs concerning marketing. We see a proven entity like Russell who presents marketing done right. He has all the accolades: Tony Robbins, the reality show The Profit, and collectively, ClickFunnel users, who have a combined four billion dollars of profit4. We see growth, sales lessons, and fast scale. We also hear the common motivational sayings about “living your dreams” that people eat up.

Once you get your funnel up and running (ClickFunnels or not), the marketing tactics and results can become addictive. When we invest more into marketing and exploit more tactics, we see one of two things: results or poor results.

To fix the latter, we double down, thinking that more marketing will solve the problem. We put more money into the marketing machine, and we believe “you must spend money to make money.” We focus solely on marketing and marketing metrics and ignore everything else. As a result, research and development, product innovation, and the people using the product get left behind. Instead of creating a better, more innovative, and original product, we create generic and forgettable commodities. We become dependent on the tactics, and we become a tactic-based business. Once we become dependent on those tactics, we slip into thinking that we can sell more by buying more marketing methods and more marketing horsepower. A business that leashes itself to marketing metrics and marketing methods blindly enslaves itself to tactics.

Putting On the Tactic Blindfold.

It’s quite possible that Jason and Garrett paid to leash their business to Russell’s directions. Keep in mind, I’m hazarding a guess. But I recognize certain signs that show I’m not being crazy with my premise.

Here’s why.

Russell offers various “inner circle” business schemes that include masterminds like Two Comma Club Coaching, Inner Circle, and Category King Council5, as well as an upsell after you buy ClickFunnels basic called Funnel Builder Secrets6 that sells for $5997. These high-cost items—the inner circle costs $15,000 to join—move you closer to Russell, and therefore, access to more tactics and guidance on how to use those tactics.

Russell’s masterminds, from what I hear, are better than most because Russell offers actual methods versus trite business platitudes. As in, you’ll get concrete marketing steps versus the common mastermind experience that is full of boasting and themes like chase excellence, do the work, have a schedule, and when everyone zigs you should zag. Investing into a Russell mastermind comes with a hefty price tag yet avails a good move for certain businesses. Russell and his team are principled and marketing savvy; he teaches proven marketing advice. In my opinion, he resides among the best marketers on the planet. But Russell offers cheap marketing tricks that can produce fast profits but can slowly make a business depend on those tricks.

Often, businesses neglect the fact that overwhelming the customer with constant selling degrades that business; it becomes kitsch, a commodity, and like everybody else. The more a business pays and believes in those tactics working, the more a business risks mutating into a tactic-based business.

This isn’t the case for every business, and I’m not saying this is the case with ClickFunnels. ClickFunnels does make it easy to become tactic based because ClickFunnels itself is mainly tactic based. This means that Russell and his team seduce users into using or buying more tactics. Yet not every business using ClickFunnels falls into a pure tactic-based business. A small few resist the pull and just use the basics.

ClickFunnels merely serves as one example out of many that shows how a business or person can blissfully fall into becoming a tactic-based business. In short, a business pays more to depend more on marketing methods and forgets about the product. And it looks like Jason and Garrett fall into the camp of buying marketing lessons and enslaving themselves to Russell’s directions.

Regardless if Garrett and Jason paid to jump into Russell’s pocket—I have no idea; it’s merely speculation based on the signs—not all credit goes to Russell. Jason and Garrett both know slick marketing tricks that print rapid profits. It costs a lot to hire Russell. As an aside, I find it troubling that Jason and Garrett—both who claim to be Alpha Businessmen—sell how to make money online by basically rehashing tactics they learned from the wizard. I argue that, while Jason and Garrett are arguably well-intentioned, they are so dependent on tactics that they aren’t creating a better product. Seemingly, they lack the business skill, self-esteem, and principles to create a better product—a product that doesn’t require patronizing their customers.

Why am I using this example? Why am I using Garrett, Jason, and ClickFunnels?

Credibility.

In any market, overused tactics sap credibility7. Albeit, Jason and Garrett, in my opinion, are arguably compensating for personal and professional insecurities. Nonetheless, the marketing methods they use, methods widely accepted as good because they convert, symbolize how to drain long-term business credibility.

Let’s unpack what I’m saying.

Garrett and Jason make their money predominantly selling to men. Both claim to be business and marketing experts. Both claim and imply they are alpha males. Both claim they wield incredible persuasion secrets, marketing secrets, business growth secrets, and copy secrets that force people to buy. They also claim to know secrets that will make men respect you. And they claim to know how to be the man that instantly tricks hot women into becoming submissive, compliant, and horny8. (I’ll clarify: Jason instructs the “Honey Trick.” He enlightens men how to trick hot women into having sex with them. For this post I won’t delve into this sad and harmful misogyny.) Forget for a moment how they primarily use and rehash tactics they learned and purchased from Russell Brunson. Remember, they utilize those purchased tactics at a high level. They follow the formula and standard sales beliefs.

Remember both sent 15 emails or more; they followed and used generic email headline tactics, body copy tactics, list-segmenting tactics, and how-many-emails-to-send tactics. Those emails sent people who clicked the link to similar sales pages over and over and over; they followed the directions: do whatever it takes to drive clicks to your sales page and test and optimize that page for the highest conversions. (Notice how the human element is removed.) Again, this is standard advice that does work.

They used tactics like scarcity, social proof, guarantees, testimonials, and polarizing statements, and they used a generic personal hero story.9 They followed the directions to send emails at specific times. Jason sends emails each day starting at 7:30 a.m., again at 5:21 p.m., again at 7:31 p.m. and again at 9:11 p.m.—the send times and quantity changes a little bit depending on his promotion, but it seems to be his standard method (what he does is quite common).

Jason and Garrett likely tracked, analyzed, tested, and obsessed about the metrics. The body copy for both the sales pitches and emails was tested. I bet they paid top people to critique their copy. When I consulted on copy, I charged $1,000 per hour. Some top copywriters charge well over $2,000 per hour. If Jason and Garrett are as smart as I think them to be, you can bet they paid a copywriter or two for a few critiques. Jason does wield some “okay” copy skill, so he may only pay for quick pass or two. Now Jason does say many call him the greatest copywriter under 40 (who that “many” is, is uncertain, and likely, his own claim).10 But Jason may not even write his copy. Matt O’Connor, owner of conversiongods.com, says, “Except for a brief period of time, I’ve written pretty much all his sales letters (everything except for his kick-ass daily emails and videos).”11 Regardless of who wrote Jason’s copy, himself or Matt or someone else, it likely received an outside critique somewhere. The same goes for Garrett.

Both pages display good, converting copy. Jason and Garrett utilize every tactic and utilize each tactic well. They are marketing pros. Whether or not they depend on Russell, they still run the plays and score touchdowns. They run trick plays. They run basic plays. They might cheat and go a little offsides, but they scramble and hustle to get wins. In fact, they run an exhausting amount of plays. They do many things many businesses believe to be a sound marketing strategy.

Humor me for a moment.

Let’s take a fictional woman, her name is Kate. Kate meets Jason. Kate gives her phone number to Jason. Instantly, Jason texts her three times per day for five days trying to persuade Kate to go on a date. As each day progresses, Jason pours on the heat. He says she needs to make a decision now. He texts her, Facebook messages her, and he DM’s her. He keeps saying it’s the last chance, and he guarantees her the best sex of her life or her integrity back. Does Jason showcase himself as a stable man? Similarly, do Jason and Garrett appear to have a stable business model?

Now let’s zoom out a little bit.

Imagine you’re buying a car. You’re deciding between two different dealerships to get the best price. But one car salesman emails you more than 15 times in a week to buy a car. We sense how stable people and businesses act. We know how a credible business acts. Using heavy-handed tactics like over-marketing saps credibility.

A product or service must carry some weight. Jason and Garrett, like many businesses, do everything by a playbook. The playbook works, but businesses who dogmatically follow it risk sapping their credibility. The tactic playbook allures businesses because it feeds a company’s self-interests to hit goals, show growth, and win. The playbook works, but we easily forget about the buyer—they become a means to an end. And often the sales tactics become those means to solve internal business problems or even personal insecurities.

An Example Of Someone Who Only Needs One Email – Not 20.

Let’s turn to Mike Cernovich.

Mike sent an email—one email for his event. That’s all he needed.

Mike fulfilled his business and marketing aims using a single email.

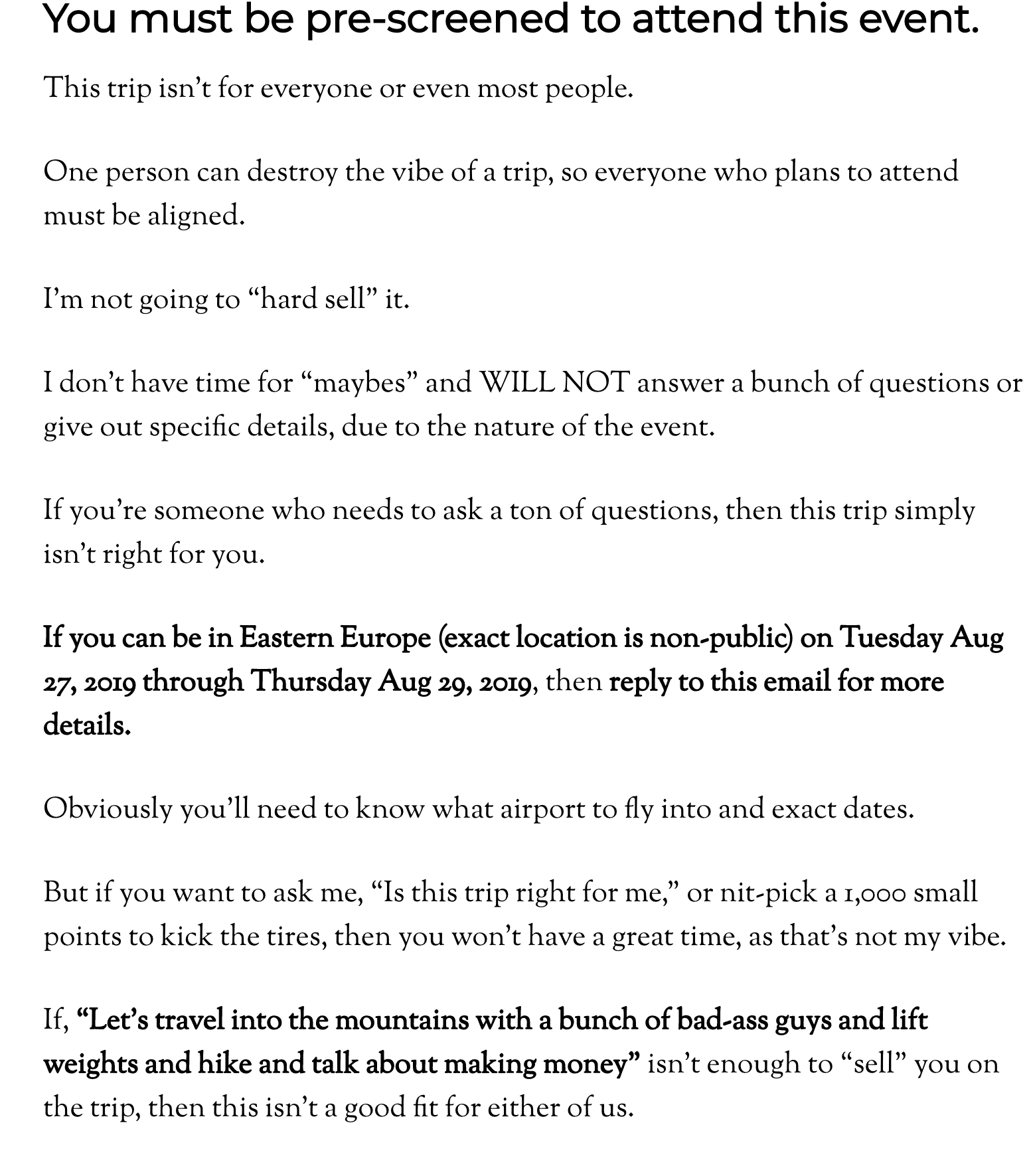

The email headline didn’t hit hard with copy. It said: The trip of a lifetime. Naturally, this raises curiosity, but he didn’t use the overused headline formulas: Hey, Goodbye, Your FREE gift, etc.

The body copy:

“He who climbs upon the highest mountains laughs at all tragedies, real or imaginary.” – Nietzsche

A private retreat into the mountains of Eastern Europe with men committed to excellence.

Mindset conversations and business planning with hard hitters.

Physical fitness challenges.

Optional night life for those who want to venture into the city before or after the event.

All of this will happen August 27th and August 29th.

Get the full details here.

- Mike

No hype, no standard sales intro of something like, “You know what separates the winners from the losers…”

Instead we see direct copy.

Mike didn’t need cheap tricks; he owns credibility with his list. I also argue that a few people signed up to Mike’s list because they strongly dislike him. That group signed up likely to troll, debate, or argue. Yet Mike still maintains credibility, even if that group dislikes him. (That credibility isn’t based on his opinions or theories; it resides in the fact that he’s a polarizing voice in mainstream media.)

Mike also doesn’t send daily or hourly; he generally sends one email per week. And those emails rarely sell something; rather they update the reader on what’s happening in Mike’s world. They share something he’s reading or found interesting, or they sometimes share his unique political ideas. And as I mentioned, he sent one email concerning his event. Translated, Mike’s business stability doesn’t require him to send emails at specific times to try to get more opens. He can send like a non-needy human. If your business is trying to send at prime email times in the hope of more opens, you may need to look into why your customers no longer pay attention to you.

Mike offered the reader one chance. Mike wants those on his list who (1) open and read his emails, (2) click his links, and (3) are committed to him. He isn’t begging for the sale; he doesn’t need to send 15 emails. He’s sending emails from a position of business stability and confidence. He knows the right person for his event is someone who has benefited from his advice and also respects him.

Mike’s sales letter was simple. A tidbit:

The copy is concise, direct, and persuasive. White page, black text, and pictures that were taken on a phone. The copy, I’ll say it again, is some of the best copy I’ve seen and studied. Mike doesn’t ask for a sale; he tells the reader to get their ass in shape before the event. He calls out the tire kicker as someone who will likely wreck the vibe of the event. He screens who he wants.

Keep in mind, Mike’s method won’t fit every business. You may need to send more than one email. You may need to use a video. Your method depends on your business model and what you sell. But you still want the right customers. You want the customers who value your product. You still want to create a business, a message, that maintains credibility.

Mike shows a balance between product and marketing. He isn’t scrambling to fill seats. As I said, he qualifies who is right for the product. Likely, and I don’t think I’m crazy in my opinion, Mike has his financials in order. He isn’t trying to drive gross profits to prove something. He isn’t enslaved to growth at all costs. He isn’t trying to prove he’s the toughest and richest kid on the playground.

Mike instead shows signs that he markets pragmatically and uses an enduring business model—he’s seeking his minimum number not the maximum number. He’s targeting what Seth Godin calls, The Minimum Viable Audience (MVA). Godin says, “The solution is simple but counterintuitive: Stake out the smallest market you can imagine. The smallest market that can sustain you, the smallest market you can adequately serve. This goes against everything you learned in capitalism school, but in fact, it’s the simplest way to matter.” 12

Many businesses or solo-preneurs think that aiming at the maximum equates profitable success. And many businesses need to generate huge sales to pay for expenses; expenses often caused from aiming at that maximum13. They believe that focusing on the MVA means they can’t generate profits or stability. But that’s the problem. If you need mega sales profits to keep the lights on, you need to take a hard look at your business model and overhead expenses. Yes, you need marketing, but your product or service must carry some weight and earn sales. Both marketing and product create demand. A great product creates demand on its own because the results are that good.

The issue with using too many marketing tactics is that they can strap a business to huge overhead costs. Then, to solve that overhead expense, most businesses try to sell more and more, grow bigger and bigger, and find and convert more and more customers. A business invests more time, more money, and more bandwidth into more marketing. Although using a heap of marketing tactics can seemingly fix short-term business problems, the tactics end up weakening your business model.14

When that happens, a company blindly mutates into a conversion-obsessed business. Every dollar, every expense, goes toward conversion metrics. This gets expensive fast, especially with direct marketing. If, for example, a company is spending over one million dollars buying media and the ad dies (or not enough people are returning to the product), . . . well, someone has to pay that ad spend bill. And often, ego and plan-continuation bias gets in the way. This bias has its roots in excessive optimism, ego, and pride. It is sometimes called “get-there-itis” because it leashes people to a plan despite it failing15. A company then starts to believe that “just one more hit sales letter will get us out of this hole.” This is the mindset that selling solves everything—no, it doesn’t. Tactics enslaved the company.

Mike shows us someone who is not enslaved to tactics. He isn’t going for straight profits; he’s offering value. He owns credibility with his audience. Mike’s product—him—carries the weight. He doesn’t need to scramble and use dozens of marketing tactics to fill seats. Even on his social media channels, he isn’t trying to constantly prove or sell himself like Jason or Garrett. Mike runs a business; he isn’t selling that he runs a business. He puts forth his ideas, theories, and products concerning politics, men, and the media.

Meanwhile, Jason and Garrett hype themselves constantly. To me, this reveals that they are obsessed with vanity metrics: conversions, gross profits, filling a huge room, and expensive email segmenting to get more clicks. They need to use every trick possible. They need those tactics to pay their overhead. They lack the marketing skill, business model, business acuity, and product strength to send one email. I argue that they’d generate less than a handful of customers if they tried Mike’s method. Not because Mike’s method is bad—it’s far superior—but because they lack the skill and product to convert.

The Formula That Stable Businesses Follow.

Mike represents a focused and concise business. With Mike, we don’t see a company chained to vanity metrics. He’s not only marketing with an MVA model, but he’s likely following a concrete marketing financial model. This is what Paul Jarvis calls the Minimum Viable Profit (MVPr).16

What is MVPr?

When you first start a business, focus on getting your numbers into the black as quickly as possible. Although this sounds like market hard and create profits, it isn’t. This method joins expenses to overhead costs. The lower those costs, the faster you can hit your MVPr. When you start out, focus on the core elements of your business. Don’t buy a ton of fancy software or get an idea, immediately rent a hip office space in downtown San Francisco, then try pitching the yet untested idea to venture capitalists.

I’ll add, use basic marketing. Write simple copy. For example, use a simple landing page that clearly calls out a common problem, a simple description of how you solve that problem, then offer your service. Here’s another way to think about it: how would you describe your core business idea to a five-year old in an elevator? Be sure to include the problem people in your market likely face and how you provide a solution.

As Paul Jarvis says, ensure your business model works on a small scale first. But what if you’re established? The same rule applies, especially with overhead expenses and marketing. What’s critical to your business isn’t the number of customers, your high conversion rates, your monthly growth, or your even gross revenue; what’s critical is a business that stays in the black and makes decisions based on realized profit and not on the expectation of profit that may happen. Again, as Jarvis makes clear, “Even when a company needs to grow, that can happen only if metrics are based on actual profit, not on hopeful profit projections.”17

I’m not saying you must stop using marketing tactics. I can’t deny how important good copy and good marketing tactics are for a company. We use these methods to sell our products, maintain a livelihood, and pay the bills. Stellar copy indeed grows a business. Analytics matter. Split testing what resonates with your audience matters. Certain metrics qualify your audience while linking them to the right message.

As any business grows, marketing methods help find a pulse of what matters to customers. Good marketing creates needed growth to pay bills, helps maintain stability, reveals what certain overhead costs to eliminate, and communicates feedback that fuels product improvement or innovation. For instance, the iPhone started out more or less with the purpose of being an iPod that makes calls. Better texting and better typing was a secondary bonus. Steve Jobs and his team didn’t plan on what we know the iPhone as today.18 Naturally, as the iPhone developed, the marketing changed, shaping the iPhone into its current function.

Even a creative-driven businesses, say writing or art based, can qualify who is right for the product. In other words, they don’t have to sell out. The creator can focus on creating what matters to them and offer their art to their audience.

No doubt, a principled and simple marketing strategy coincides with business health. In fact, in our modern era, the most successful businesses—Amazon or Facebook—didn’t follow standard marketing principles or sales advice. Today, super specific knowledge and the focus on a specific area combined with a basic marketing plan—and I mean the absolute rudimentary basics—grows a business.19 As the business grows and the product develops, the marketing develops with the product. How does that marketing develop? Better copy, better social media influence, a better email system to handle more customers, and better testing to better serve customer needs. This marketing plan doesn’t require guarded secrets or covert persuasion tactics; it requires basic marketing and products or services that deliver results.

We Live in an Era of Me-Too Marketing.

Jack Reis and Al Trout, authors of the legendary marketing book, Positioning, warned against creating me-too products.20 They theorized that businesses become obsessed with creating a better product or a knock-off product, and the money never gets spent on what matters: marketing.

To an extent, I agree. Often, entrepreneurs build an echo chamber around their idea and work on a product that they think is incredible, when in fact it’s either too complicated, or no one really wants a $78,000 bazooka that vanquishes mice from a garage.

Simple marketing early on can help test an idea cheaply and provide feedback about the product. For instance, the mattress company Tuft and Needle tested their idea with a simple online ad to see if anyone would buy. Then, they constantly tweaked and perfected their mattress based on feedback and simple marketing methods. In so doing, Tuft and Needle flipped the mattress industry.

They had an idea and created a small, basic sales pitch for a new style of mattress to see if they had a concept. One person bought before they even had a mattress; they immediately returned that person’s money but asked for feedback. From there, they tested and developed their mattress, checking their pulse via marketing so as not to become hidebound inventors until the product was perfect. They used basic, I mean utterly basic—a landing page, simple copy, and a buy button—marketing to test and develop their product. By the way, their website is a stellar example of copy and marketing. 21

Reis and Trout explained that me-too products create a problem. But today, we face a different issue: due to better marketing metrics, a common obsession with sales and profits, we now have too much me-too marketing. In other words, most marketing—ad copy, email marketing, influencer marketing, commercials, and more— has become generic.

A common marketing notion—especially among those in the marketing departments or attending motivational seminars— says that the only way to grow a business requires using incredible marketing strategy, utilizing any method to capture huge amounts of leads, or attempting hip influencer marketing. This is why a platform like ClickFunnels allures many businesses. All the tactics are locked, loaded, and ready to be aimed and unleashed.

But the growth-at-all-costs mindset misleads businesses to mirror other businesses’ marketing strategies. And yes, the tactics spark gross profits and new leads. But companies who use a restrained approach show far better Return on Investment and exponentially better Long-term Customer Value. Granted, you can’t be exclusively focused on long-term marketing.

You can and should utilize certain tactics because they offer feedback. But if you’re so focused on day-one dollars, getting as many new leads as possible, and expanding into as many new cities as you can, you slip into a short-tail business model. You must strike a balance, and often this comes down to overhead expenses, simple marketing, and generating results that create word-of-mouth buzz. It takes courage, planning, and skill to commit to a better product and to use marketing basics.

You might think I’m nuts. Most business advice or motivational people like Grant Cardone direct you to double down and invest on marketing. Or we hear stories telling us why we must acquire as many customers as fast as we can. Yet, enough evidence shows I’m not nuts.

Let’s look at a famous example, Pets.com. Pets.com showed incredible potential. They spent a fortune on marketing and growth. And grow they did. They used the best marketing tactics and rapidly acquired customers, but they had weak business fundamentals. Even though they had the marketing numbers a Gary Vaynerchuk could only dream about, they couldn’t meet demand, the product stunk, and they lacked a sustainable financial model. Now they’re known as one of the biggest dot-com-era busts.22 As of this writing, the hip company WeWork looks like it will fall victim to “growth at all costs without a viable business model” as well.

Basic, Focused, and Delicious.

Let’s look at another famous example—an example done right.

Halo Top Ice Cream stuck to basic marketing, a viable business plan, and its principles. In doing so, they disrupted the entire ice cream industry.

Let’s unpack Halo Top.

First, a bit of Halo Top background.

Halo Top is a low calorie ice cream. It presents itself as a reasonable and tasty option for a health conscious ice cream lover. The company founder, Justin Woolverton, started Halo Top as a side business. He was a lawyer and ice cream lover. He was trying to cut back on sugary and super processed foods. He never started a business before Halo Top, but he began tinkering with ice cream recipes in his kitchen for 18 months. He began slowly.

He figured fellow ice cream lovers would perhaps want an ice cream they could enjoy as a regular part of their diet. He offered and sold his product here and there at certain retail locations. But he intended to receive customer feedback versus marketing for straight growth.

He wanted to see if he had an idea, then see how people reacted to his ice cream. He didn’t follow the Gary V. quit-your-job mentality and jump into the ice cream market. He avoided trying covert persuasion secrets to 20x his business. Woolverton kept his day job. During those 18 months, he experimented with different ice cream ingredient variations—based on his taste buds and customer feedback—until he hit what he thought was a good tasting formula.

Once he had the formula, he called a few distributors. And he ran a bootstrapped side business. Again, he did not quit his day job. He had enormous student debt, and he poured all Halo Top earnings back into the product—NOT into the marketing. After a year or so, Halo Top became stable enough for Woolverton to quit his job. He then partnered with another lawyer and friend, Doug Bouton. This move was risky. Both had a lot of debt and both kept putting the earnings back into developing the product and not the marketing tactics.

At this point, most companies would attempt massive growth via aggressive marketing to solve the debt; Woolverton and Bouton didn’t. They also had opportunities to be bought out; they said no. Instead, they worked on creating a better product. Then they raised money while also still improving the product based on customer feedback. As in, they didn’t stop at the idea that says “Make the product good enough and then sell it.” They treaded pragmatically. After they attained sales over 1.4 million dollars they—against common advice—stopped trying to get capital. They figured that they either had a business model and product, or they didn’t. They could go out and raise more capital, but they felt it was time to see if the product could carry most of the weight.

They tried their best to get the product in front of people, continue to receive customer feedback, and let the product sell itself. Most people who tried their ice cream loved it. Eventually people started raving about this product through word of mouth, articles, and on Instagram.

Woolverton and Bouton didn’t get “ambassadors” or make affiliate deals to have an influencer say they love the product. They wanted the results to speak for themselves. Most marketers would dogmatically tell them this is a horrific idea and maybe remind them of the cliché “The product graveyard is filled with incredible products that had terrible marketing.”

Today, Halo Top sits among the top three ice cream sales in America—a position that Häagen Daaz and Ben & Jerry’s dominated for years. Some months, Halo Top earns the number one spot. They now employ one hundred people—the majority of whom work remotely—and as of 2017, Halo Top earned $347 million in sales.

Halo Top illustrates how basic business fundamentals, product development, and altruistic marketing can combine into a thriving business plan. And they started with one key ingredient: ensuring the product got results.

How the Generic ‘Hot-Shot’ Copywriter Would Ruin Halo Top.

Now, let’s play a little devil’s advocate.

I’m going to show, through my copywriting lens, how a copywriter would think about Halo Top. And I’ll show tactics, the “guarded secrets,” Halo Top could have easily picked and used—tactics that would have cranked initial sales and profits but would have blocked the company from becoming a top-three ice cream brand.

Let’s begin.

Halo Top makes a low-calorie ice cream. When we think low calorie, we often think diet, weight loss, and low taste. Halo Top focused on taste. They focused on delivering a tasty ice cream to a health-conscious ice cream lover. Meaning, Halo Top wanted to give ice cream lovers a tasty choice they could enjoy as a regular part of their diet.

Let’s look at how a copywriter thinks about naming the product.

Halo Top was originally named Eden Creamery. A lawsuit forced Woolverton to switch the name to Halo Top.23 Woolverton said this forced the company to create a better name, and I agree, Halo Top is the better name; nonetheless both names are solid.

Why? They are both generalist names. A product or service name conjures an image, a reaction. Albeit, this isn’t the case with all products, but on the whole, a name still paints an image in the potential buyer’s mind.

The name Eden Creamery brings to mind a guilt-free promised land. It makes us think that we can eat something without guilt—before that dastardly snake persuades us with email marketing to eat the apple of 10% discounts.

The Halo Top name paints an image in two ways. One, it implies that a Halo is hovering a few inches above our heads, meaning being good. Two, a golden seal encircles the top of the package, making it look like a halo covers the ice cream. Halo Top offers us two ideas: one where the customer is being good, and one where the product is being good. Neither image hammers the consumer. It doesn’t virtue signal like, KETO CAKE.

With Halo Top, we get to make a choice. While ice cream is widely considered a guilty treat, we can choose an ice cream that’s tasty and healthy.

Had Woolverton picked a name like Skinny Cow, Halo Top would immediately be lumped into the “diet” category. This advice would follow the common idea—target your niche market. That advice is good, however, most follow it blindly when it may not apply to a particular product or service. For instance, at a Jason Capital Summit Event, a guest speaker or Capital himself will likely preach lessons like “Find your tribe” or “Get your customers; your hungry market.” And maybe a copywriter will even tell the Gary Halbert anecdote: find a hungry crowd. Translated, this means that you should find your specific niche and dominate it, which of course, is an abstract, vague, and one-plan-fits-all businesses marketing idea.

Had Woolverton attended a “Team Capital Mastermind” and presented his healthy ice cream option, he’d have heard plenty of others tell him to go into the weight loss market. Even outside a mastermind, I wouldn’t be surprised if plenty told him to go after the diet market.

However, a name depends entirely on the market, so a general name like Halo Top performs well because it attracts a larger variety of health conscious people. On one end, the Halo Top name raises curiosity to someone looking to lose weight. On the other end, a fitness competitor who loves ice cream extends the glad spoon to a tasty treat that works with their dialed-in caloric intake.

By using a general name that didn’t attempt to target a core niche, Halo Top presented a reasonable option.

While Halo Top attracts a mass market, it still focuses on the sophisticated buyer. The brand appeals to the health conscious person who also happens to be an ice cream lover. This is why Halo Top didn’t pick the too general “Acme Ice Cream: Flavor Inside“ or “Fat Burner Ice Cream: Get Abs Like A Cobble Stone Street—Solves Other Life Problems Too!” The former ends up forgotten. The latter triggers feelings of overwhelm as well as thoughts of “This probably tastes like shit.” Or, more common in weight loss, people think, “I can eat as much of this ice cream as I want and blast off fat.” When that doesn’t pan out, they say, “It didn’t work for me; I put on pounds,” and they move on.

By using a general name that didn’t attempt to target a core niche, Halo Top presented a reasonable option.

But then Halo Top committed what many marketers would consider a sin: they wrote IN BIG NUMBERS the calorie amount on the pint. Labeling something Low-Calorie gets mixed reactions. It’s much easier to label the magic, like Keto, or label to a cultural or regional diet, like Mediterranean, because people assign—misappropriate—their biases that those people or that culture are healthier.

Most people believe something else works rather than concerning themselves with calories. Many feel the idea of calories-in and calories-out is a sham, despite basic biology. Similarly, people think that low calorie equates low taste. And many believe that low calorie means they can eat more of it; thus they end up eating too many calories and later say that calorie counting or eating less didn’t work.

In short, calories receive mixed and often negative reactions. And as far as the retail shelf space product placement, most low-calorie options tend to be shit sellers and are placed on shelves where one has to hunt to find the item, even at stores like Whole Foods, which appeals to a more health conscious buyer.

Halo Top, despite what a marketer would say about the calorie label, went after health conscious ice cream lovers. Similarly, they understood how most people—health conscious or not—eat ice cream.

When you buy a pint of ice cream, you plan to eat the pint. A standard pint easily packs a 1000-plus-caloric bomb. If you look at a standard pint’s average serving size, often it’s around a half cup. And the pint will contain around four servings. And each serving might be 270–320 calories.

Now, if you’re a fellow ice cream lover like me, you’ll think, “A half cup of ice cream? Bullshit. It feels like a small spoon’s worth.”

When people buy a pint of ice cream, they plan to eat the pint of ice cream. This is a reality Halo Top understood and where Woolverton generated his idea for Halo Top. He wanted ice cream as a regular part of his diet. He figured other ice cream lovers must be aware of the fact: when you crack open a pint of ice cream, you eat the entire pint. Therein lies the issue: you eat the pint; you feel guilty. You know you ate too much; you think it was gluttonous. It stinks. You avoid ice cream for days and weeks.

Halo Top created a lower calorie choice that ice cream lovers could enjoy. Halo Top didn’t leash themselves by labeling their ice cream low-cal; instead, they put the entire calorie amount right on the pint: 280, 320, or 360. The ice cream lover is likely not calorie counting; however, the ice cream lover understands a 320 calorie pint of Peanut Butter Cup packs way less caloric tax than the Ben and Jerry’s pint equivalent—which packs 1,260 calories. This means that the buyer is a bit sophisticated. They like ice cream. They’re bummed or know they shouldn’t eat Cherry Garcia every night, but they wish they could.

Halo Top offers that person an option. It isn’t Skinny Cow—which triggers reactions that the ice cream probably tastes like poorly flavored chalk—and it isn’t Keto Miracle Cream. Instead, we find a reasonable option that solves this common situation: the hopeful idealism we feel when we say we’ll stick to that measly 2/3 cup serving size of Ben & Jerry’s Peanut Butter Brownie Core—420 calories—but we know how, yet again, we’ll end up eating the entire pint and know all too well the eventual self-loathing and guilt we’ll feel after.

Halo Top offers a choice instead of promises and claims. Halo Top uses simple copy: “We think it tastes good and you might too.” 24

Woolverton conceived the Halo Top idea when he looked to reduce his intake of refined carbohydrates and sugar,25 so he had the diet avenue. He could have targeted the weight loss niche. He could have also capitalized on the current Keto Fad. A copywriter could have easily created a story about how Woolverton discovered an ice cream that shredded 68 lbs. in one month and saved his life. Since Woolverton looks like he didn’t struggle with his weight, the copywriter could have either fabricated a Woolverton story, capitalized on the GQ article where the journalist lost ten pounds eating nothing but Halo Top26, or just completely made something up.

The copywriter could have also taken an ingredient from Halo Top say, Spirulina, or the current fad, Turmeric, and found studies to slant the copy toward weight loss and claim miracles. In other words, the name could have “targeted” his niche audience with “Turmeric Fat Melting Cream: Burn Fat Fast.” Or maybe, if Woolverton decided to load the formula with fat, he could strip away the faux pas low-calorie label and gone with “Keto Cream: Get Shredded on Ketones!” or “Bulletproof Mentalist Cream: Get Smart, Get Fit, Live Longer, Induce Envy.”

Most marketing and sales advice teaches us to make promises and claims. The idea goes: promises and claims reassure the customer and prevent buyer’s remorse.

Halo Top doesn’t promise or claim. In certain markets, a promise does matter, but not every market requires promises or claims. Halo Top could have made claims since most “health foods” often make a claim or a promise. They could claim that “it tastes amazing and zaps off fat.”

They could capitalize on the GQ article where a journalist ate nothing but Halo Top and lost weight.27 That article could have easily been a two-for-one tactic: stick the label “as seen on” on their landing page for credibility, then stretch the weight loss into a near miracle. Now, they also could have made slighted attacks against Ben & Jerry’s or Häagen Daaz or even Skinny Cow. They could say how the other ice creams make you fat. If they had Jason Capital writing, or an Agora writer, maybe they would say that “Other ice creams cause cancer and kill you or make you weak” and “Halo Top raises your status.”

Halo Top stayed away from tactic-based claims and promises. I personally find claims and promises in a sales message a short-term profit trick that often cheapens a brand. Generally, the more promises, guarantees, and boasts a sales letter or sales message needs, the less the product offers—a fact most marketing forgets.

The Core Basics—These Teachings Still Work.

But when you study famous ads by David Ogilvy and Claude Hopkins, they stay away from empty promises, grand claims, and selling language. Claude Hopkins does make some promises. Claude promises with a caveat—try it and see—much like the Halo Top copy “We think it tastes good, and you might too.” Translated, we believe in the product; we worked hard on the product; we like it; people like it; you might too.

Many Hopkin’s ads featured another promise: if you don’t like it, no worries; simply send it back for a full refund.

The promise is subtle. In certain Ogilvy ads, like his famous Rolls Royce Ad, he doesn’t make any promises. Instead, he tells you, if you’re not into a Rolls Royce, check out a Bentley. Translated, we understand the Rolls Royce can seem snobby; we know it’s expensive; we know this car isn’t for everybody—if it isn’t for you, here’s another option you might like. Ogilvy doesn’t try scarcity tactics to convince the buyer. He’s qualifying the right buyer.

Halo Top easily had the option to create product demand via direct marketing tactics. For instance, they could have written long posts on their Instagram page and maybe even a few sales letter style videos on Instagram. They could have created compelling calls to action driving you to their landing page. From there, you could sign up for their newsletter. And maybe, they could offer an eBook 7 Secrets To Eating All The Ice Cream You Want And Losing Weight. Next, they could have sold you their ice cream. They could have created a persona—Halo Top Harry—and Harry would send you a ton of emails about their ice cream.

Since Halo Top is sold on Amazon, they could have boasted about their reviews. How? They could use a tactic many marketers use when they—or a marketing publishing agency—release a new book. Halo Top Harry could have asked you to buy a certain amount of the new pints of ice cream, then if you left a five-star review, they would offer you a gift of some sort.

Then, they could have leveraged those reviews and put them on the Halo Top landing page. Also, tactically, those reviews would raise their rating in Amazon metrics. Or, they could have used another trick and asked you to order a few cartons with 36 pints. If you did, and left a sterling five-star review, you earned another bonus. This way, they could have padded early sales to get a better standing in best sellers. Halo Top didn’t do this. Halo Top grew primarily through word of mouth, Instagram chatter, and a lot of Woolverton’s and Bouton’s hustle in retail markets.

Halo Top didn’t fabricate their word of mouth; instead the product carried the weight. Meaning, Halo Top could have paid influencers or offered affiliate deals to bloggers and influencers. This common tactic unfolds like this: hey we pay you; you say you love the product, and we’ll give you a kickback. Often this fact is not disclosed, or the influencer masks their intention by calling themselves a “brand ambassador.”

When Halo Top started generating millions of dollars in gross sales, they had this option and had it in spades. But at that time, the product struggled to maintain its consistency while in transit to retail stores. Between the time it was made and when it arrived at the retail store, it didn’t taste great.28 At this juncture, Halo Top could have followed the dogmatic “good enough” advice. They could have poured the money into brand ambassadors and influencers. By pushing the marketing instead of making a better product, they likely would have attained more sales and faster growth. But the product would likely have been lumped in with other mediocre-tasting low-cal ice cream.

Consequently, by putting that money into marketing instead of improving the product, they would have boosted their overhead expenses, expenses to handle the new leads, and marketing software expenses. They may have experienced incredible conversions, then focused on those fast dollars. I predict, had they followed this common route, they’d be stuck way behind Skinny Cow. Their product would be mediocre, likely not good enough to stay in retail stores. They maybe would try to solve this with better segmenting, aggressive affiliate deals, or more marketing software.

But Halo Top adhered to their principles; they wanted to make an ice cream everyone could enjoy as a regular part of their diet. That meant that they had to make a better product. They focused on taste. They listened to customer feedback.

Both Woolverton and Bouton were lawyers. They both had legal career capital that they leveraged to get their products in the right stores at the right eye-level. What is legal career capital?

First, let’s focus on career capital. Cal Newport coined the term, and I think it fits. The theory states that if you want a great job, you need to build up rare and valuable skills to offer in return. This means that you bring a craftsman’s mindset to your work instead of a passion mindset. What is the passion mindset? Get an idea, quit your job, dream big, double your dreams, ignite your passion, and live your dreams—CHASE EXCELLENCE!!!!29 Often, this is about what your job or career can give you. The craftsman’s mindset? Cal Newport aptly states, “a focus on value you’re producing in your job.” In some careers, this could be focusing on sharpening a skill like coding, writing, or art. For something like Halo Top, the aim was making a great product that people loved. The aim wasn’t “Disrupt the ice cream industry!” This would be an example of the passion mindset. Instead, Woolverton and Bouton focused on the craftsman’s mindset—creating a tasty ice cream—and they leveraged their legal career capital to help get that ice cream to the right people. I mention the legal career capital because it’d be easy to say—they had an idea and went with it! If you can dream it—DO IT!!!

Wrong.

Both Woolverton and Bouton were established lawyers. While the love for ice cream mattered, they had some prior career capital. They had skills in basic rhetoric, debate, and understanding contracts. This legal career capital set gave them an edge when talking to distributors and handling struggles with vendors. Likely, they had also developed some persuasive talent. They weren’t fiddling with spin selling or hardcore closing tactics; they knew how to debate, present, and rhetorically engage the other side. This gave them huge amounts of leverage. Now, while they wielded this lawyer wand, they still focused on being small. They focused on taste, steady growth, and constant feedback from customers. They let the product carry the weight, and any marketing enabled the product. They avoided scale at all costs; they didn’t harbor grand plans to take over Ben & Jerry’s.

Halo Top focused on their market. They used simple marketing tactics, focused on the product, and made sure to get the product in the hands of their customer. And Halo Top became an “overnight” success. It took them seven years, which, in the grand scheme of things, is a fast, meteoric rise.

I say this because most online schemes about making money fast and one-plan-fits-all marketing lessons and tactics, promise fast money and huge growth. They ignore the fact that most successful companies, and even bloggers who earn a healthy income, often take over ten years, and most of those companies use pragmatic marketing basics suitable to their business. They use simple copy and offer a simple choice. They don’t fall prey to “If you’re in control, you’re not going fast enough” nonsense. They listen to customer feedback and grow with the market. Whereas, if you look at the statistics of people and businesses who suddenly experience a windfall of cash and growth or those who focus on growth at all costs—athletes, celebrities, lottery winners, WeWork—most are broke, facing enormous challenges, bankrupt, and sometimes the business is gone inside of five years. 30

As we see, Halo Top easily could have used strong-handed marketing tactics. They could have invested the money they raised in marketing. They could have gone after conversions, created targeted funnels, and hired celebrities. But they didn’t. They focused on taste, crafting the product so their market liked it, and getting the product in the hands of their market. Despite all the analytics, metrics, and copy testing, the product delivered customer results that generated word-of-mouth sales, and that good tasting product turned Halo Top into a $347 million dollar company.

Sound Marketing Tactics and Copy Qualify Your Customers.

While sales and growth are kept in mind, growth isn’t the only concern. Good marketing works like compounding interest. It works like an Exchange Traded Fund. While growth is important, steady, long-term growth is ideal. You look to keep your costs low and grow as the business grows. Companies like Halo Top or personalities like Mike Cernovich qualify who they want.

Yes, Halo Top now reaches a mass market, but they still focus on what makes them successful. Anything new is questioned, tested, and either used or discarded. They focus on taste, customer, and primarily, a lot of word of mouth. Mike Cernovich doesn’t need a video of him saying “just win” or standing in Las Vegas next to fancy cars and wearing a shirt that says “Warrior.” He qualifies who he wants.

Paul Jarvis says you meet customer demands and marketing demands as you grow. 31 This means, you don’t just start wildly automating your email marketing, paying celebrities, and spending big bucks on marketing, all in hope of future profits. Yes, the copy matters, but if you’re spending $30,000 on a sales letter before you have a sale, something is wrong. The product should be able to generate enough steam, and your marketing can grow along with it. I’m not saying don’t write copy, but don’t create marketing and see what happens; first see how the product or service gets results.

Mike Cernovich doesn’t need to badger his list or badger his clients. He doesn’t need to claim his Trump persuasion secrets—in fact Cernovich is revered by the Trump camp.32 No matter what you think of Mike, he owns credibility with his audience. He even flags the attention of those who hate him.

I don’t subscribe to Mike’s ideologies, but his marketing is worth studying. How did he become both a notorious and loved personality? The answer lies in simple yet potent marketing. Mike, on the whole, markets transparently. Similarly, Halo Top isn’t making miracle claims, huge promises, or paying celebrities for a trite endorsement. Neither are obsessed with the tactics. Both are obsessed—in their own way—with a better product. Today, in this hyper-connected era where product reviews and digital connection create more and more transparency, the better product or service holds up.

As Harvard Business Review reports, since 2012, no company is safe without spending more on R&D or creating a better product.33 Halo Top, and yes Mike Cernovich—love or hate him—exemplify this fact. And it’s not just limited to them. Economists show that R&D, even university research, leads to far more viable long-term products.

Let’s look at a less polarizing, and more ideologically normal online personality, James Clear. James Clear is the best-selling author of Atomic Habits. He writes about better habits and discipline. He exists in a market often rife with hucksters. Clear could have easily gone down the Jason Capital path by hammering miracles and how to become stinking rich. Instead, Clear researches viable habits. And it’s why he’s one of the most successful bloggers on the internet today. He barely sells; he isn’t hitting people with “HARDCORE COPY.” He simply researches viable habits. He’s a great writer. He’s spent years researching and writing, and he offers true value. He stayed away from “content marketing with valuable content!!!!!” He doesn’t badger his email list with “goodbye” or any of that nonsense. He focuses on making a great product.

Product results matter.

I argue that Amazon triggered a big change in the way we interact with products. We can easily see results other people get. Transparency is quickly making its way into the way we buy anything. Results and a good product carry a company now. Companies or individuals like James Clear who invest in making a better product are investing in their career capital and creating credibility. A company standing purely on marketing tactics stands on a house built by old cards.

Marketing should enable and present a solid product. Good copy simply defines a product’s best features. Split tests aren’t done in the hope of making the launch successful but in the hope of better connecting to customers.

Whether a company is large or small, a craftsperson’s approach generates this balance between product and marketing tactics. You market to present the product’s best features—the problems the product solves, what the product entails, and why it’s not a horrible idea to use it. And you use those direct marketing tactics not only to help sales but also to gain feedback.

You gain feedback on two ends. One, yes, you must sell the product. Things like split testing can help develop your copy and your marketing message. It can make your message clear to those who want your product. That is vital. Two, you can use the direct marketing tactics to get direct feedback from your customers. Direct marketing allows companies of one person or mega corporations to experience a more one-to-one relationship with people. Of course, people who buy Tide aren’t thinking of a relationship with Tide. But through marketing, Tide can learn who buys the product, what the customer’s experience is like, what trends are happening, and what problems Tide can better solve. This is just like a blogger who can see how their product creates different results and how they can improve on the product.

The marketing methods must suit your brand. You only gain advantage with marketing tactics when you know how they best grow, present, and qualify.

As I said, writing copy is tough. If you’re selling an online course, your first crack at copy will likely suck, even if you follow some good copy formulas. The only way you will get better is if you split test a few things and then see if it increases sales. But you must then see who you’re attracting. Why did they buy, and what results are people getting?

Although Amazon doesn’t need a lot of copy, the company is constantly seeking to make a better customer experience. While Amazon’s aim can be detrimental to the employee experience, the goal has always been to benefit the customer. They test this with various methods of delivery and try to make the buying experience easier. The dogmatic marketing advice of sell and always be closing falls flat today—it wrecks your credibility. It’s not conventional. It’s not dated advice. It’s just unquestioned voodoo. Ad greats like David Ogilvy and Claude Hopkins never followed the always-be-selling advice. They presented a product’s strength.

Let’s return to our “Alpha Men.” Jason and Garrett exemplify shrewd marketing. They follow the common directions, and they teach common marketing advice. But their product is marketing themselves, and they do this by constantly marketing. Jason and Garrett are just boys who are boasting. They are like the guys in a Clint Eastwood Western. They have all the fancy guns and all the big claims of being awesome.

But then Clint shows up. Clint’s character shows experience, purpose, and value. He doesn’t need vanity. Jason and Garrett don’t have the credibility to market like Mike Cernovich. Sure, they market with passion and promise huge benefits, but their followers would leave them in an instant if they only sent one email and a sales letter like Mike. Why? Because their product is nonexistent.

Mike, on the other hand, steadily grows. The product is him and his conviction. The sales letter instantly qualifies who he wants, and he only needs to send one. Jason and Garrett can’t qualify; they don’t have the strength to do so. They are consumed with marketing tactics. Like Pets.com, they’re enslaved to marketing.

I’ll leave it to you to decide which marketing tactics are the good, the bad, and the ugly.

- https://www.jcapitaltraining.com/sales-page27246123?utm_source=625aemail&utm_medium=email ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Trump ↩

- https://www.jcapitaltraining.com/iga-ig-agent34geg?utm_campaign=&utm_medium=email&utm_source=613b ↩

- https://www.ClickFunnels.com/ ↩

- https://twocommaclubcoaching.com/open-now ↩

- https://app.ClickFunnels.com/funnel_builder_secrets/?cf_affiliate_id=318721&affiliate_id=318721 ↩

- https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-oren-klaff-project/id1465682077 ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fKTA_qTL7SQ ↩

- Why Successful People Don’t Teach Success ↩

- https://www.jcapitaltraining.com/ccc-optin27689507?utm_campaign=&utm_medium=email&utm_source=92a ↩

- https://www.conversiongods.com/jason-capital/ ↩

- https://seths.blog/2017/07/in-search-of-the-minimum-viable-audience/ ↩

- https://hbr.org/2017/01/curing-the-addiction-to-growth ↩

- https://hbr.org/2019/09/dont-let-metrics-undermine-your-business ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunk_cost ↩

- https://pjrvs.com/mvpr/ ↩

- Company of One: Why Staying Small Is The Next Big Thing For Business, Paul Jarvis. Houghtin Mifflin Harcourt 2019 ↩

- Digital Minimalism: Choosing A Focused Life in a Busy World, Cal Newport. Portfolio Penguin, 2019 ↩

- https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2015/03/the-present-and-future-of-marketing.html ↩

- Positioning, Al Reis and Jack Trout. McGraw Hill 2001 ↩

- https://www.tuftandneedle.com/about/story/ ↩

- Company of One: Why Staying Small is the Next Big Thing for Business, Paul Jarvis. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2019 ↩

- https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-halo-top-icecream-20170915-story.html ↩

- https://halotop.com/ ↩

- https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-halo-top-icecream-20170915-story.html ↩

- https://www.gq.com/story/halo-top-ice-cream-review-diet ↩

- https://www.gq.com/story/halo-top-ice-cream-review-diet ↩

- https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-halo-top-icecream-20170915-story.html ↩

- pg. 42, So Good They Can’t Ignore You by Cal Newport. 2012 Hatchette Book Group ↩

- https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/310166 ↩

- Company of One: Why Staying Small is the Next Big Thing for Business, Paul Jarvis. Houghton Mifflin Court, 2019 ↩

- https://twitter.com/donaldjtrumpjr/status/849240401974308864?lang=en ↩

- https://hbr.org/2019/05/rd-spending-has-dramatically-surpassed-advertising-spending ↩